57STUDIO는 예술 아카이브를 바탕으로 독창적인 미디어 콘텐츠를 제작하는 스튜디오입니다. 국내외 주요 미술관과의 협력으로 전시 영상을 제작하며, 공연 예술 영상, 영화제 출품작, 그리고 기업 브랜드 필름 등 예술적 가치를 담은 다양한 미디어 작업을 선보이고 있습니다.

Selected Work는 57STUDIO의 최근 관심사와 우리의 예술적 비전과 고유한 색깔을 반영한 아카이브를 선별하여 모았습니다.

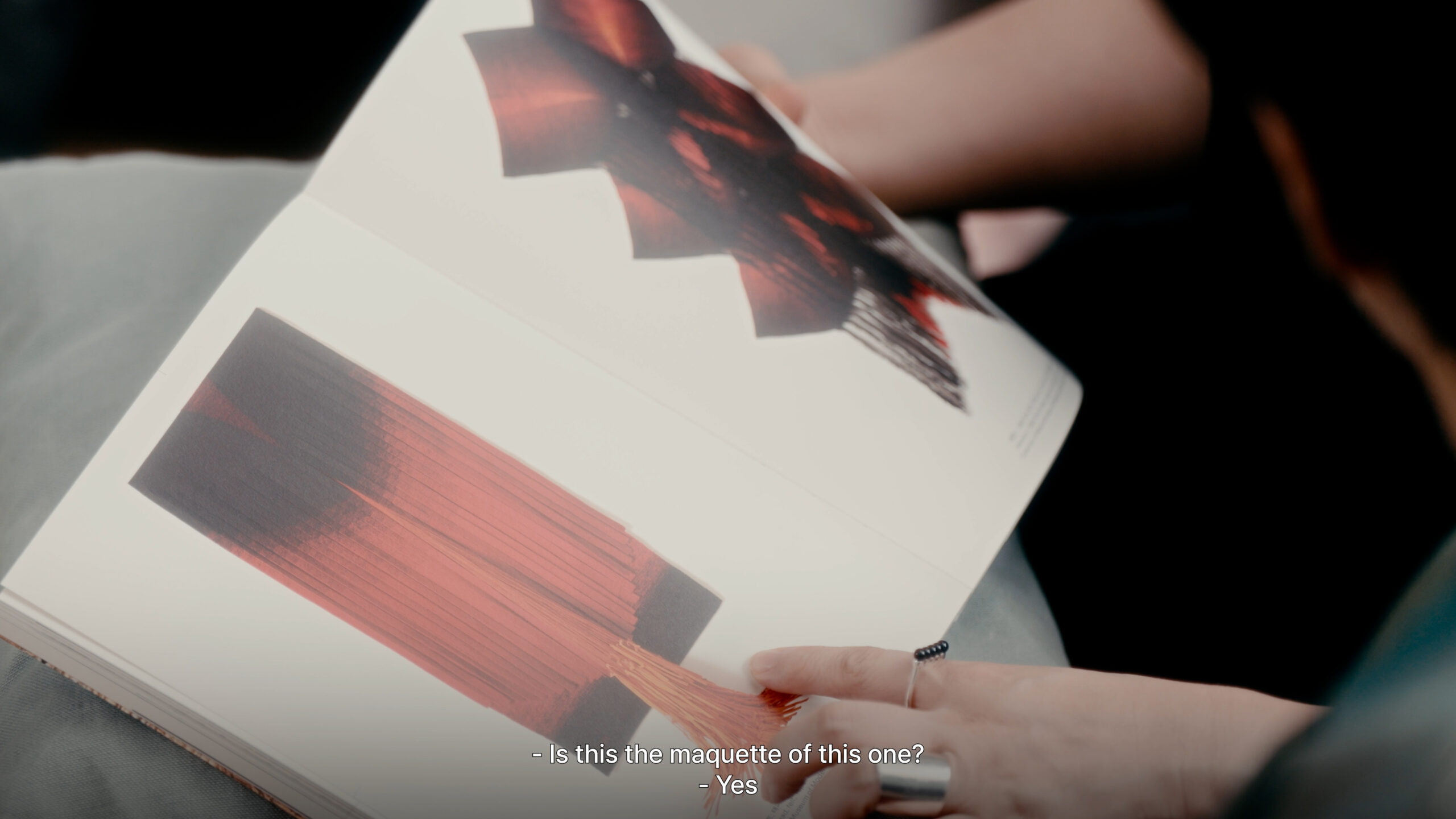

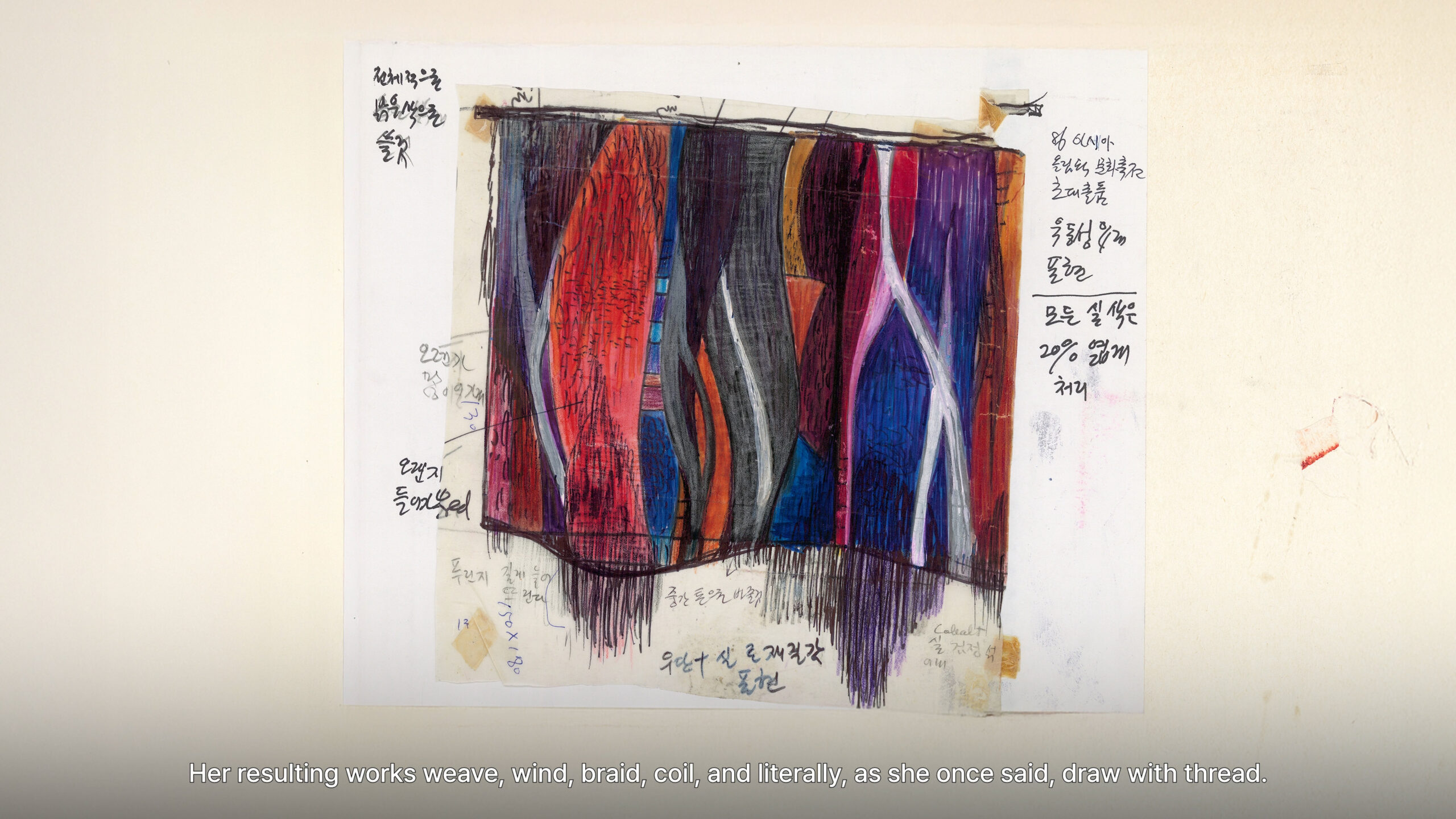

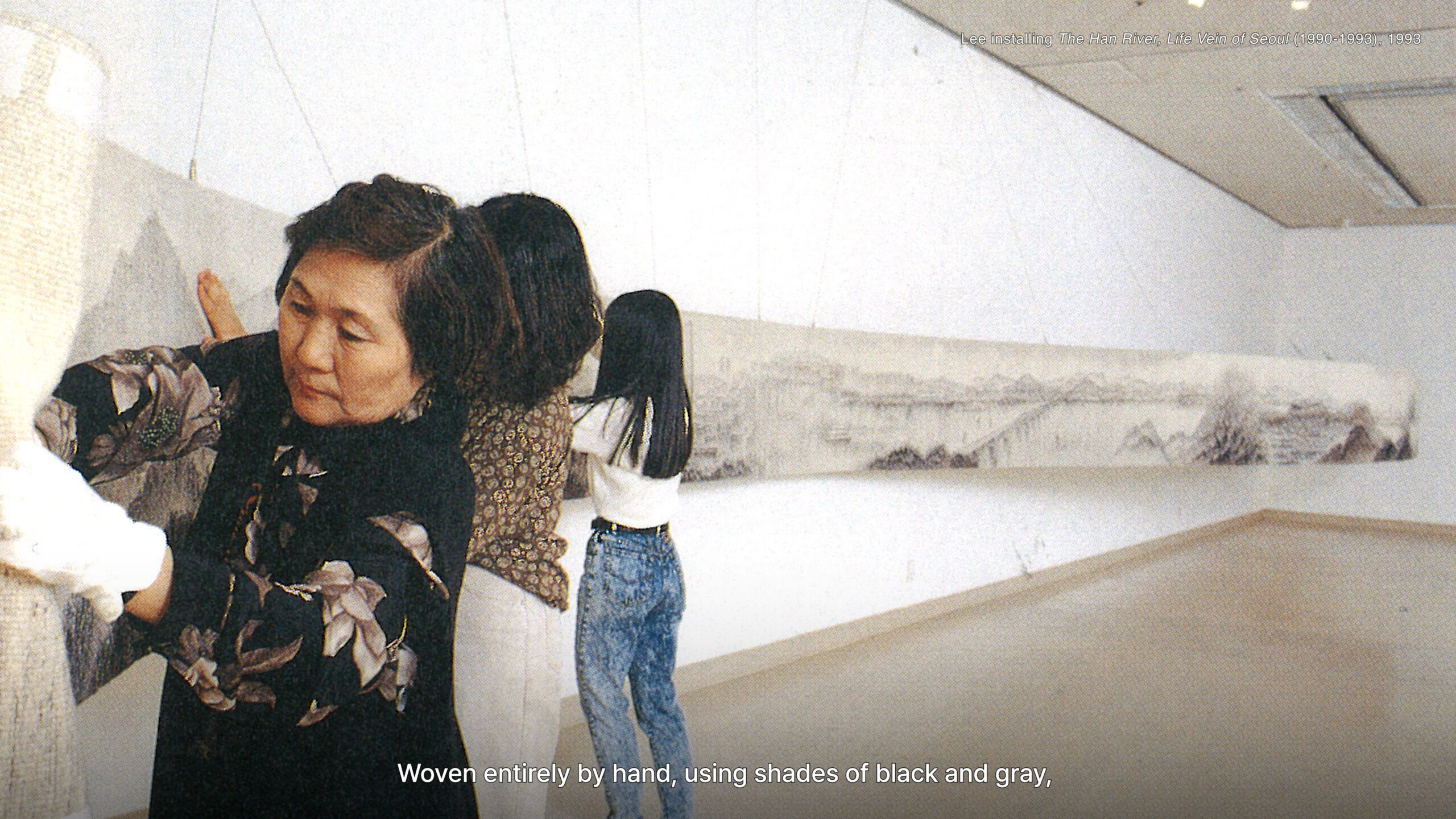

57STUDIOis a creative studio that produces original media content based on art archives. We collaborate with major museums both domestically and internationally to create exhibition videos, and we present a variety of media works imbued with artistic value, including performance art videos, film festival submissions, and corporate brand films.

Selected Work is a curated collection of archives that reflects 57STUDIO’s recent interests, our artistic vision, and unique style.