작업 소개

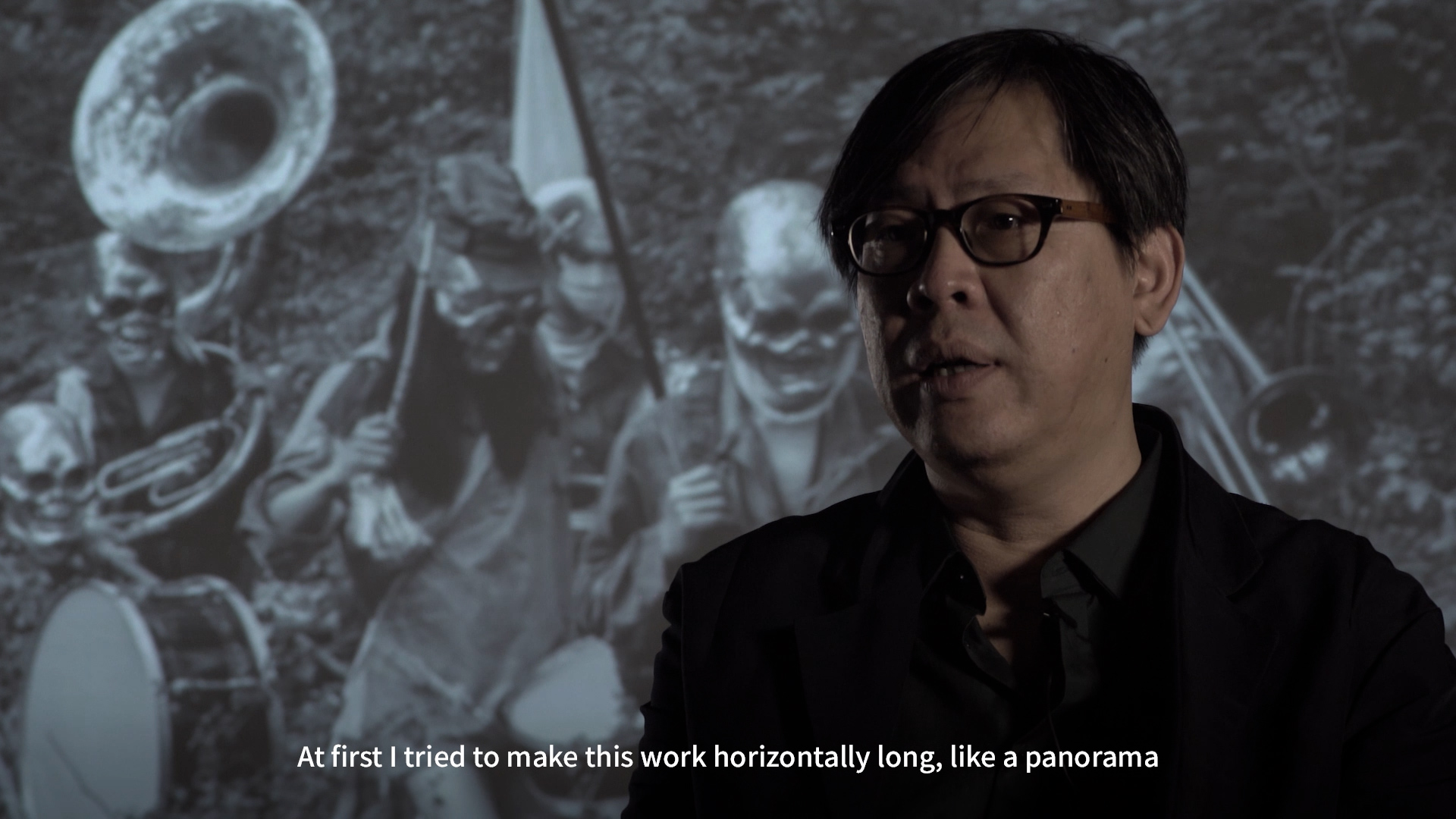

57STUDIO는 국제갤러리에서 열린 박찬경의 개인전 《안녕 安寧 Farewell》을 기념하여, 작가의 작업 세계를 심층적으로 조명하는 아티스트 인터뷰 영상을 구성 및 제작하였습니다. 이번 영상은 박찬경이 지속적으로 탐구해온 전통, 냉전, 분단이라는 주제를 바탕으로, 그의 비평적 시선과 예술적 사유를 보다 입체적으로 전달하는 데 중점을 두었습니다.

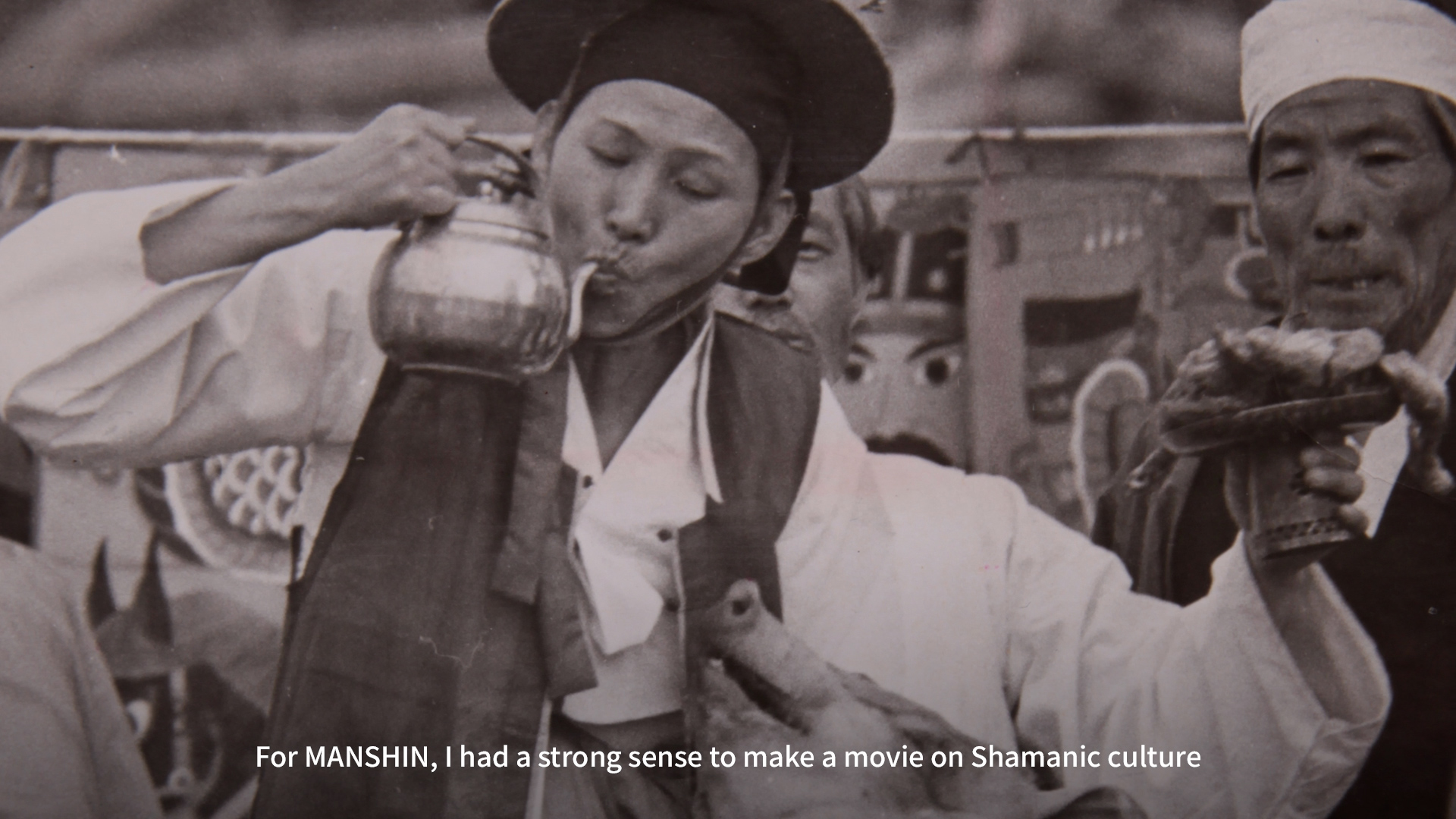

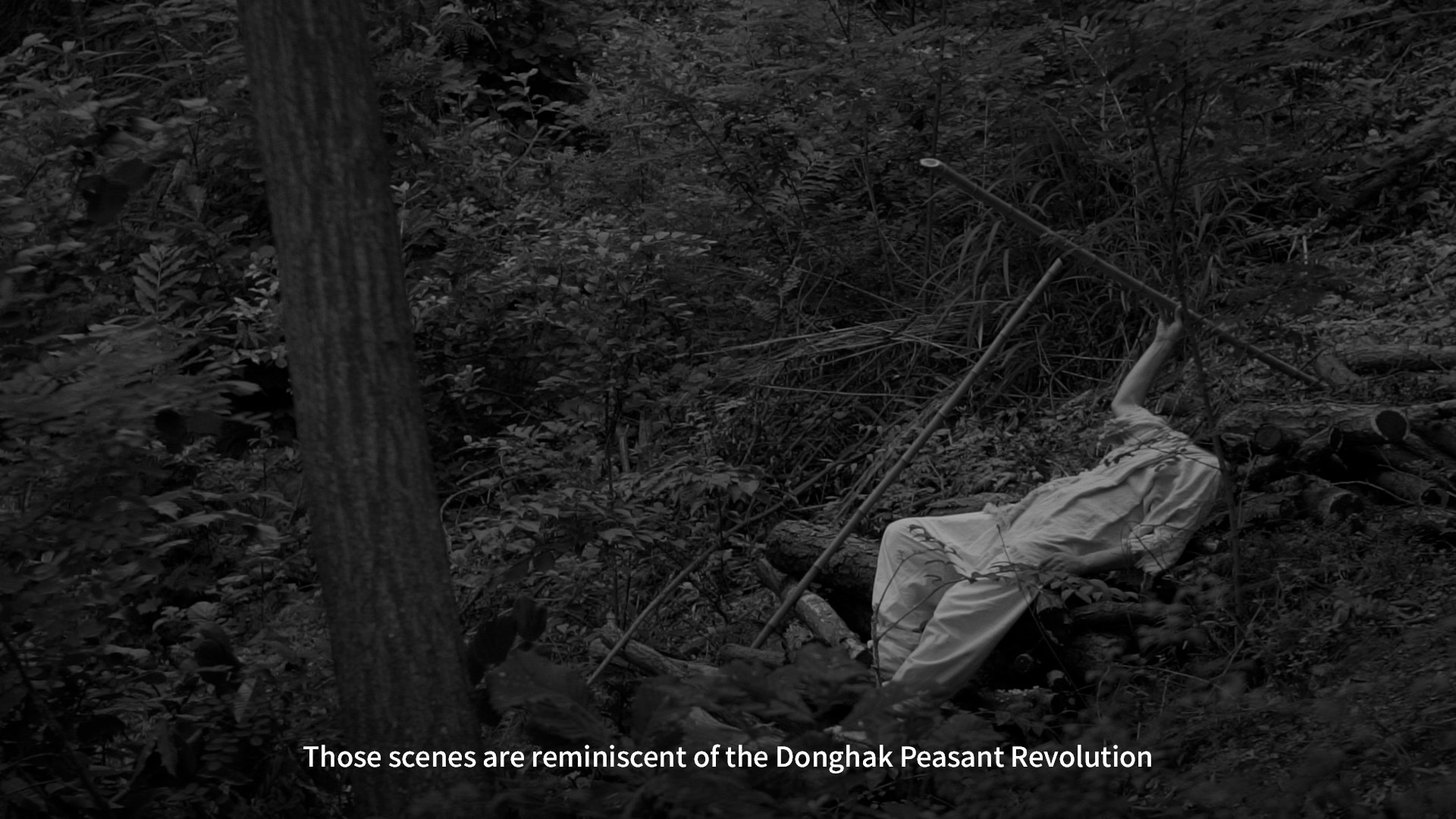

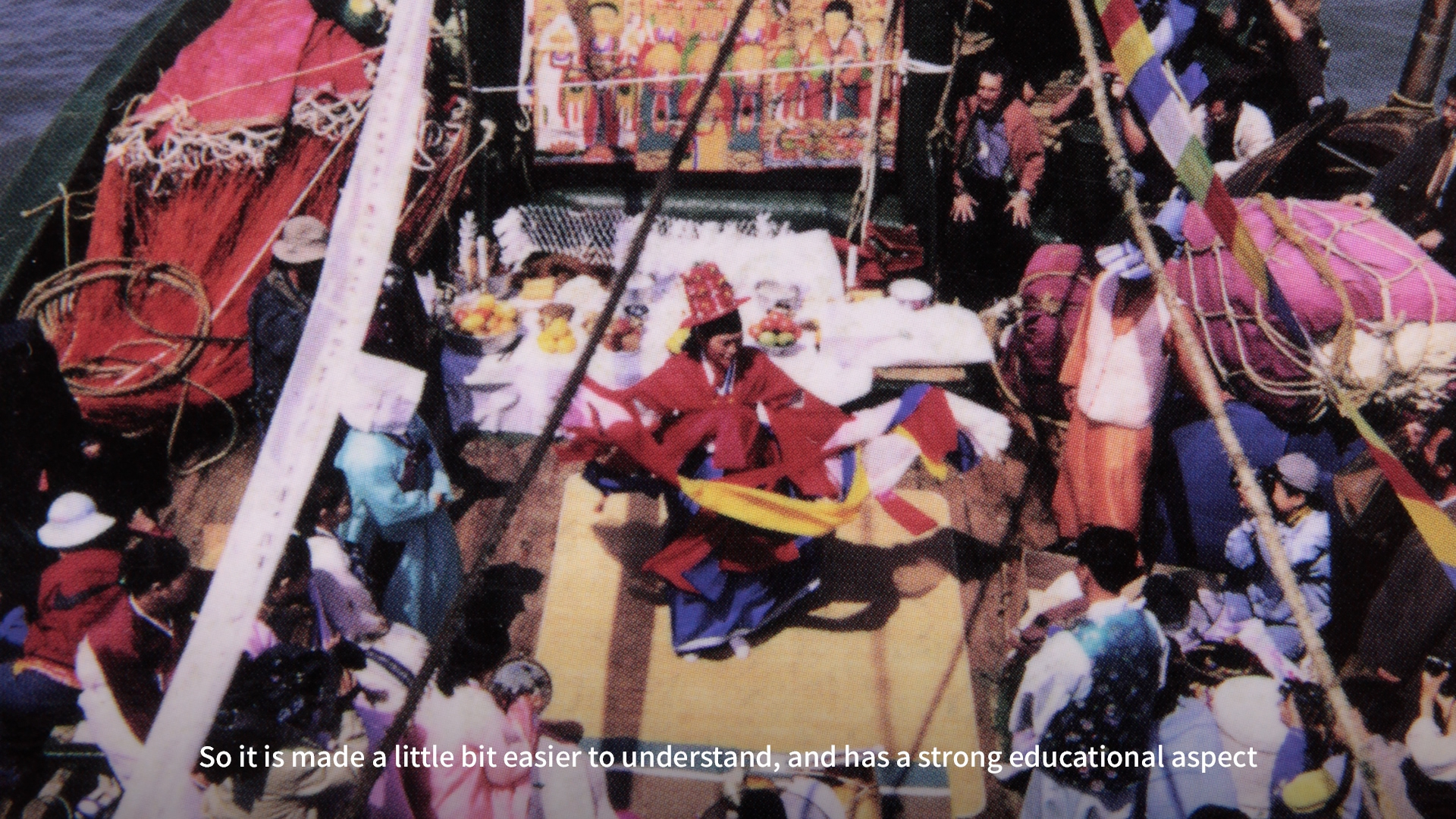

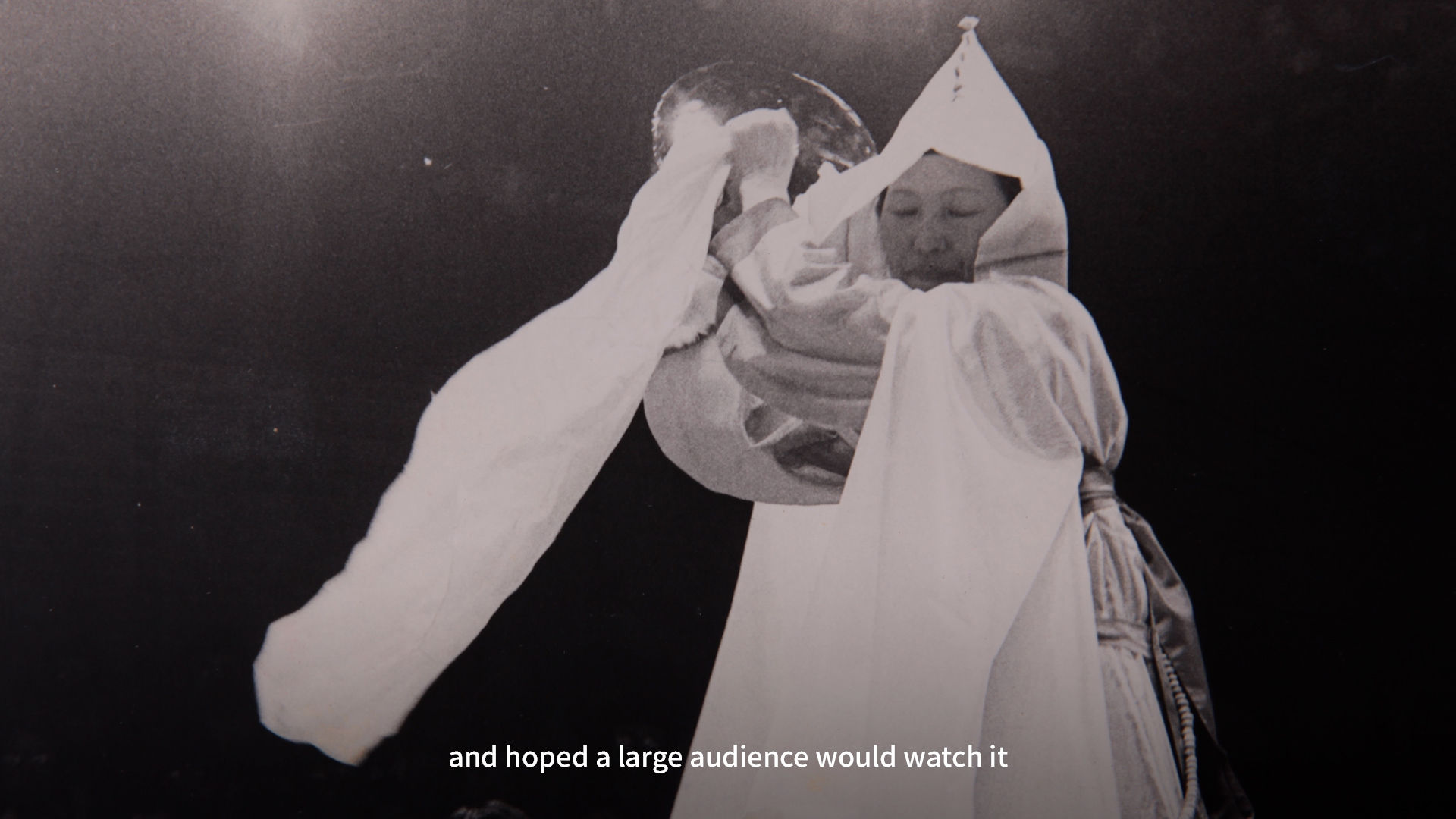

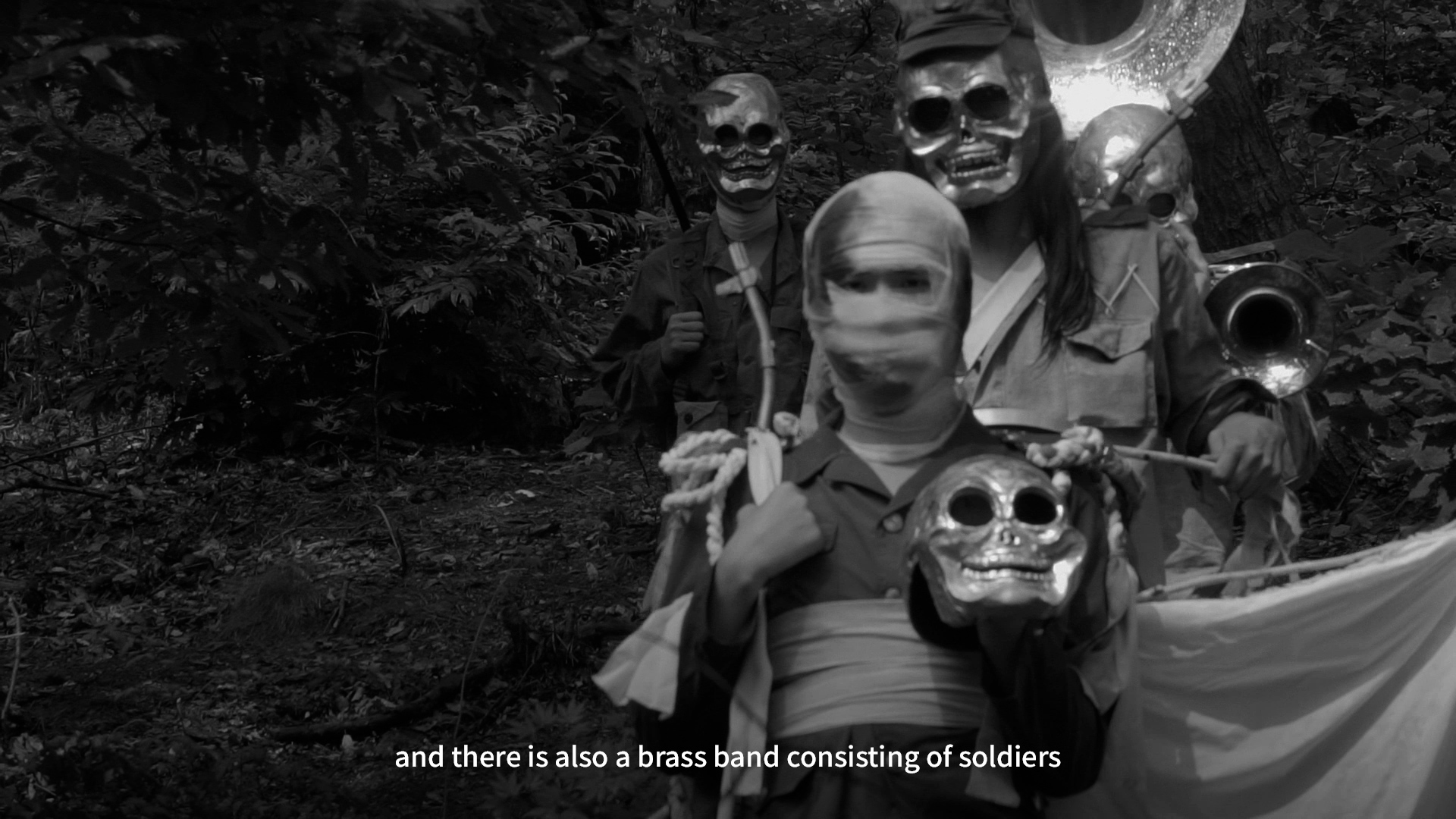

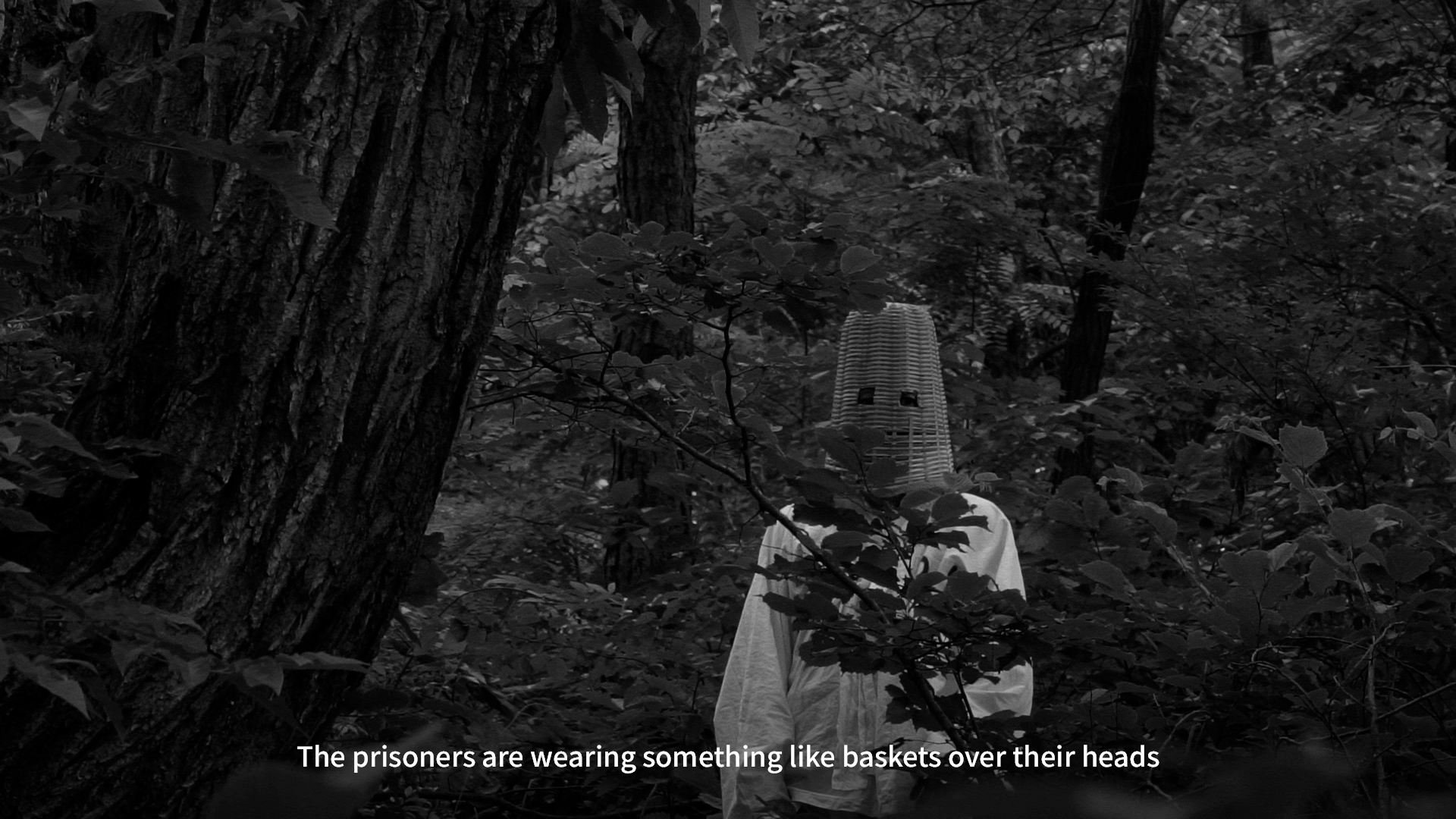

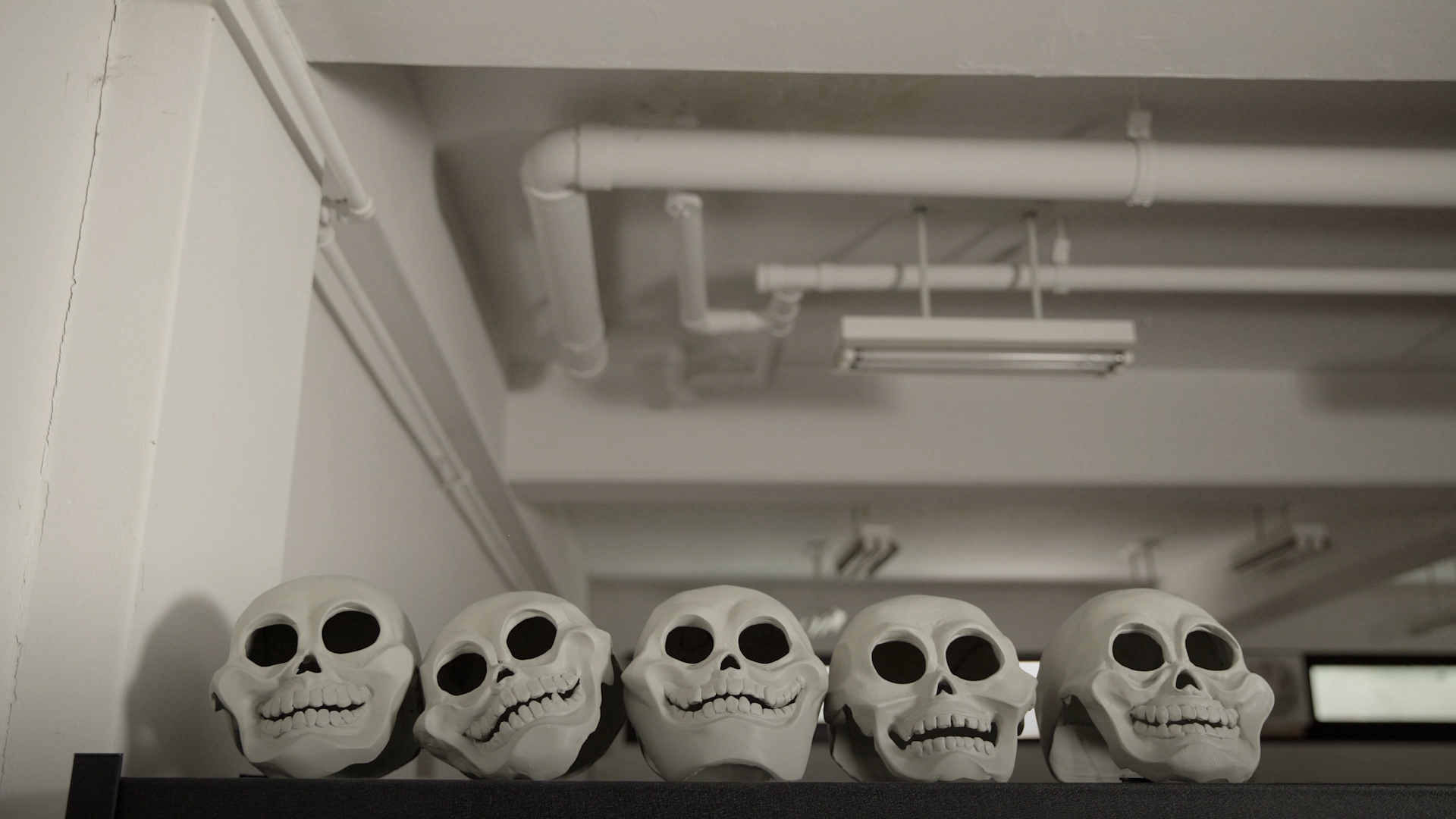

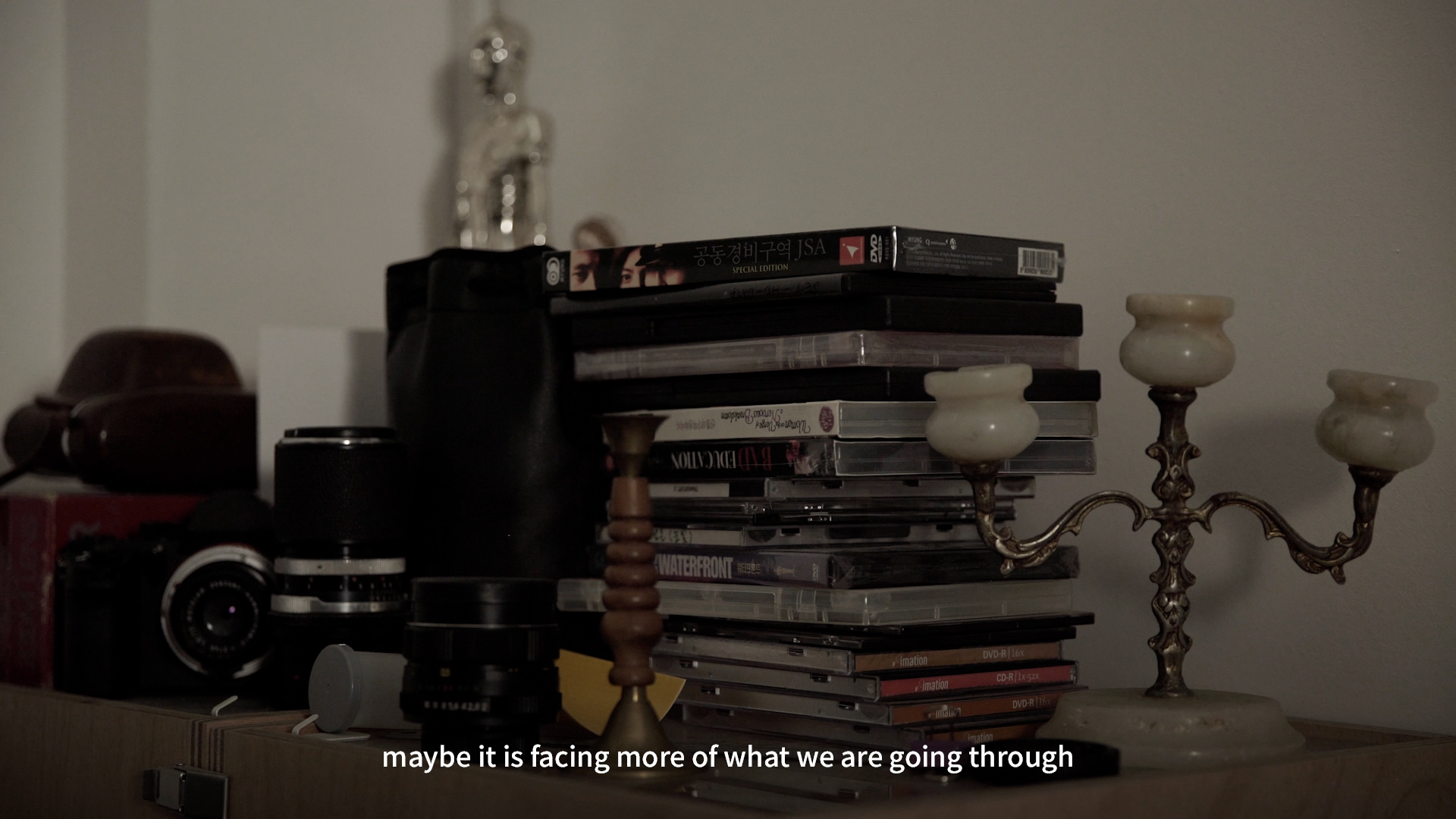

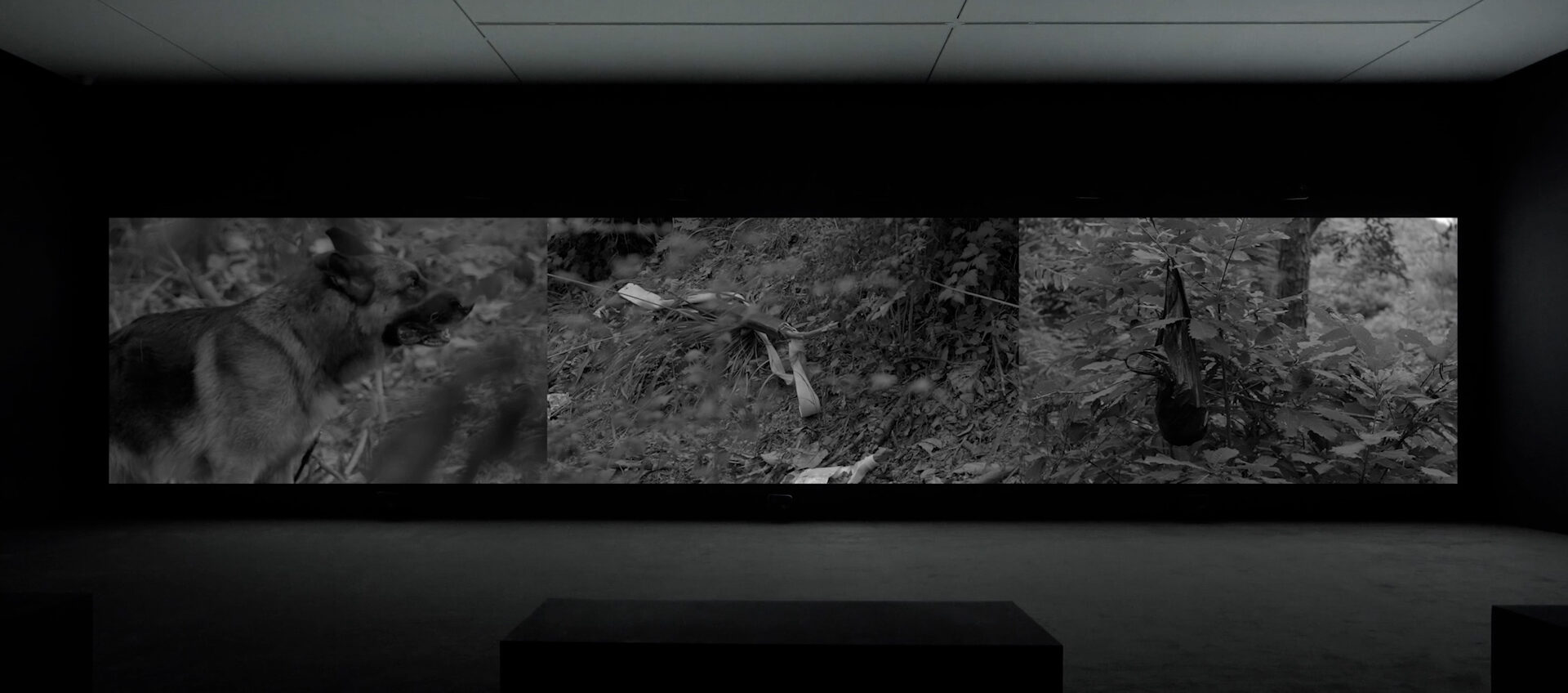

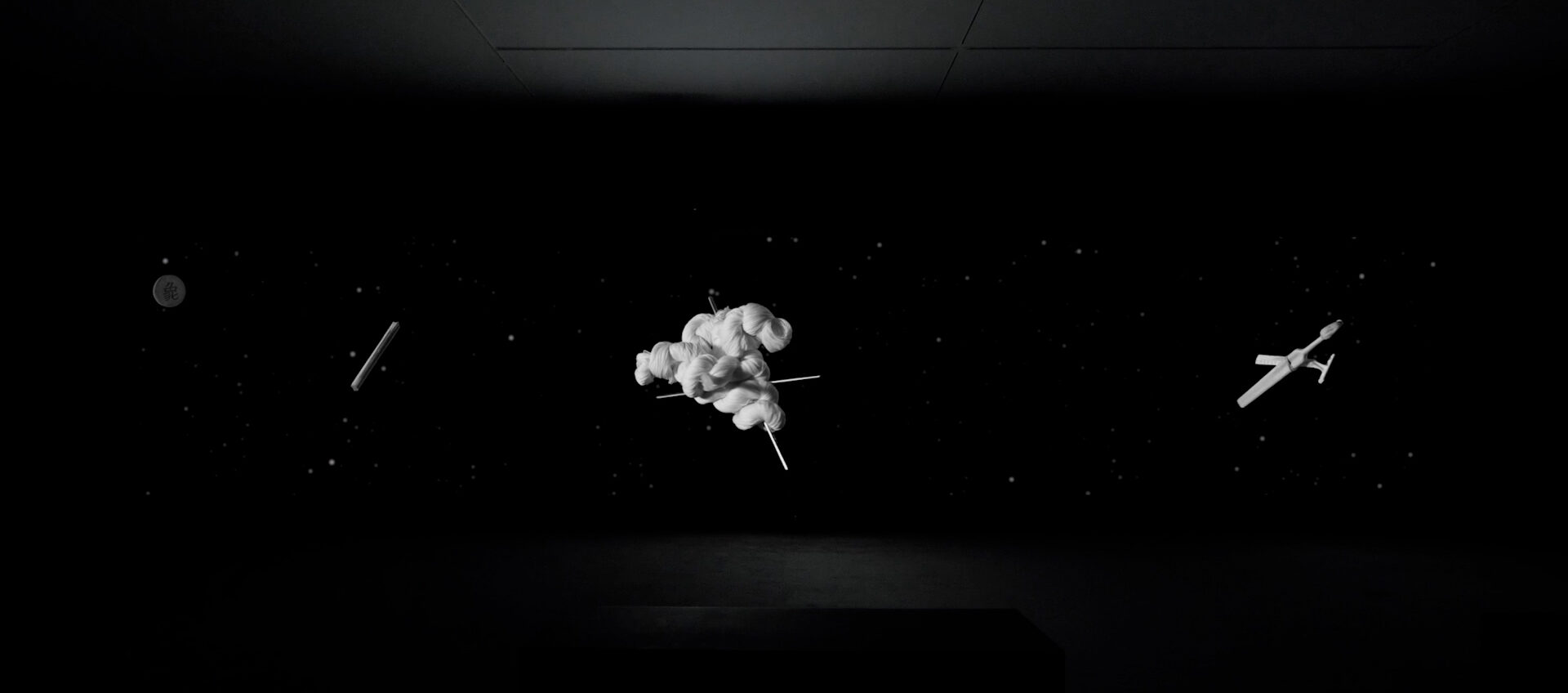

박찬경은 서구적 근대화와 맹목적인 성장 속에서 성찰 없이 달려온 한국 사회의 구조를 역사적 층위와 종교, 민간 신앙의 시선을 통해 비평해 왔습니다. 이번 전시에서는 대표작인 3채널 비디오-오디오 작업 <시민의 숲>(2016)을 비롯해, <작은 미술사>, <승가사 가는 길>, <밝은 별>, <칠성도> 등 신작 13점을 선보이며, 그의 복합적인 미학을 드러냈습니다.

57STUDIO는 박찬경의 전시 공간을 구성하는 시각적 리듬과 작가의 내밀한 설명을 영상에 유기적으로 담아내어, 작품의 맥락과 작가의 철학이 함께 전달될 수 있는 인터뷰 시리즈로 완성하였습니다.

57STUDIO produced an in-depth artist interview video in celebration of Park Chan-kyong’s solo exhibition Farewell (安寧) at Kukje Gallery. This video focuses on conveying the artist’s critical perspective and layered artistic thinking, built upon his ongoing exploration of themes such as tradition, the Cold War, and national division.

Park Chan-kyong has consistently critiqued the trajectory of Korean society, which has advanced through Western-style modernization and blind growth without sufficient reflection. His work reflects on this history through the lenses of religion, folk beliefs, and layered historical narratives. The exhibition presented 13 works, including the three-channel video-audio piece Citizen’s Forest (2016), alongside new works such as A Short History of Korean Art, On the Way to Seunggasa Temple, Bright Star, and Chilseongdo, which collectively reveal the complexity of his aesthetic language.

57STUDIO structured the video to organically integrate the visual rhythm of the exhibition space with the artist’s introspective commentary, creating an interview series that communicates both the contextual depth of the works and the philosophical grounding behind them.