작업 소개

‘인간, 일곱 개의 질문’은 모든 예술의 근원인 ‘인간’을 돌아보고, 21세기의 급변하는 환경과 유례없는 팬데믹 상황에서 인간으로 존재하는 것의 의미를 고찰하며 미래를 가늠하는 전시입니다. 57STUDIO는 큐레이터 전시 해설 영상과 함께 참여 작가들의 인터뷰 시리즈, 인문학자들의 렉처 시리즈를 구성하고 제작하였습니다.

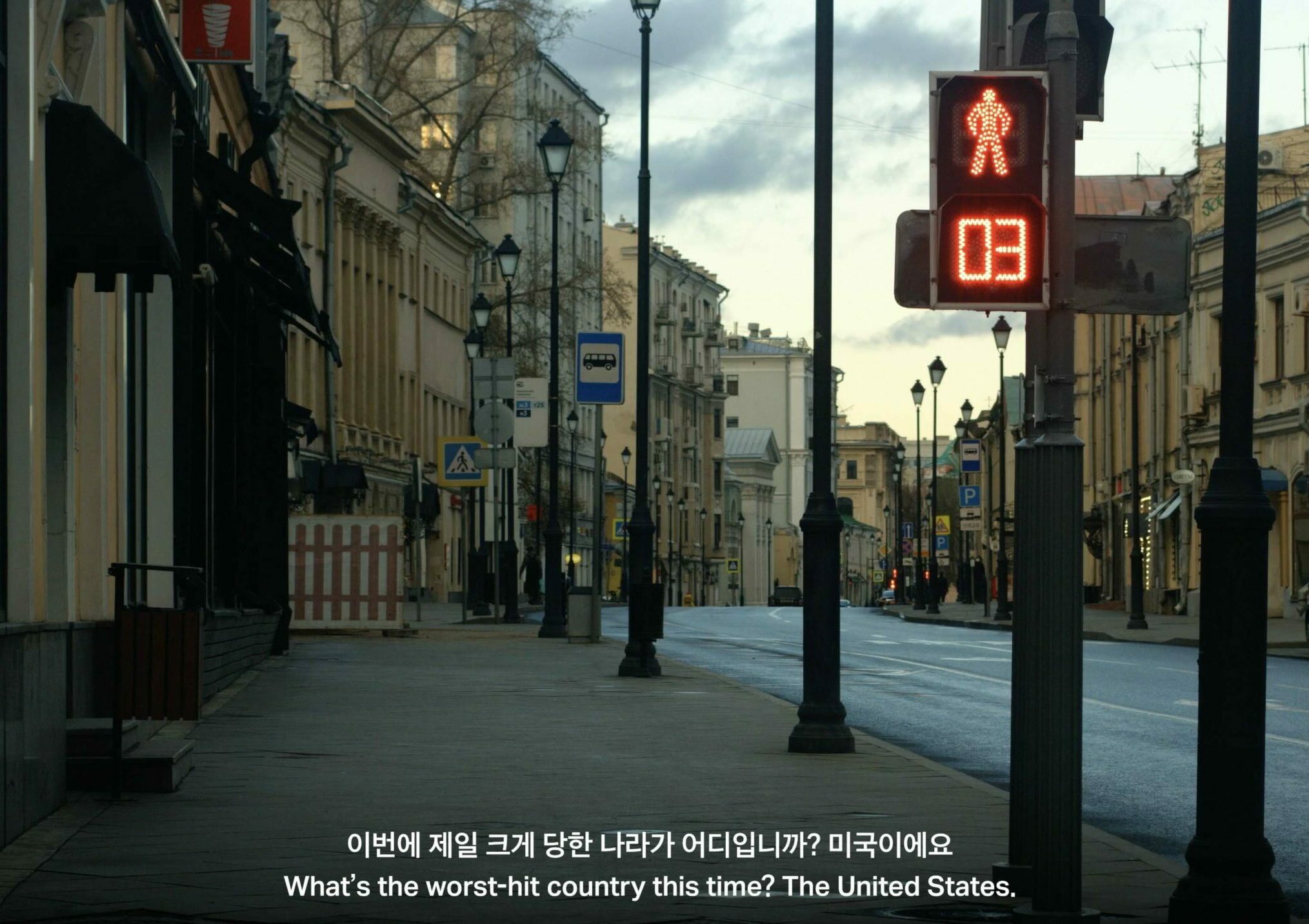

인간이란 무엇인지, 코로나 팬데믹과 인류세를 마주한 인간이 스스로에게 던져야 할 가장 중요한 질문은 무엇인지, 국내외 석학과 참여 작가들에게 묻고, 그들의 통찰을 영상에 담았습니다.

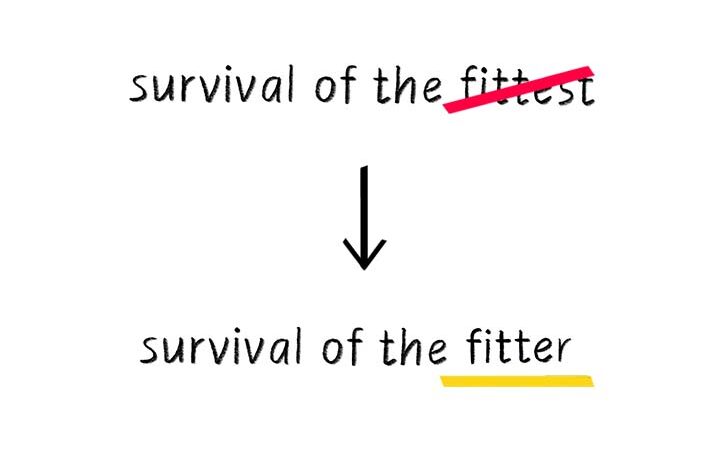

인간전 연계 인터뷰 시리즈의 마지막 영상에서, 생태학자 최재천 교수는 인간이 자연을 지나치게 경쟁적 시각으로만 바라보았다고 지적합니다. 그는 최종 승자가 독식하지 않더라도 생존할 수 있는 방법이 있다고 말합니다. 그 해결책의 단서는 최재천 교수가 제안하는 새로운 인간의 학명, 호모 심비우스 (Homo Symbious)에 담겨 있습니다.

“Human, 7 Questions” is an exhibition that reflects on “humanity,” the foundation of all art, while contemplating the meaning of human existence in the rapidly changing environment of the 21st century and the unprecedented pandemic. The exhibition seeks to provide insight into the future.

57STUDIO produced a series of curator-led exhibition commentary videos, interviews with participating artists, and lecture series featuring humanities scholars. We asked both renowned international and domestic scholars, as well as participating artists, the most important questions humanity must ask itself: What does it mean to be human, and what questions must humans confront in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Anthropocene? Their insights were captured in these videos.

In the final video of the interview series connected to the Human exhibition, ecologist Professor Choi Jae-cheon highlights that humanity has viewed nature too competitively. He explains that there are ways to survive without the winner-takes-all mentality.

The key to this solution lies in Professor Choi’s proposed new scientific name for humanity, Homo Symbious.