1. Changes Brought by AI

Curator Yi Soojung:

As you may already know, I will first briefly introduce our two speakers.

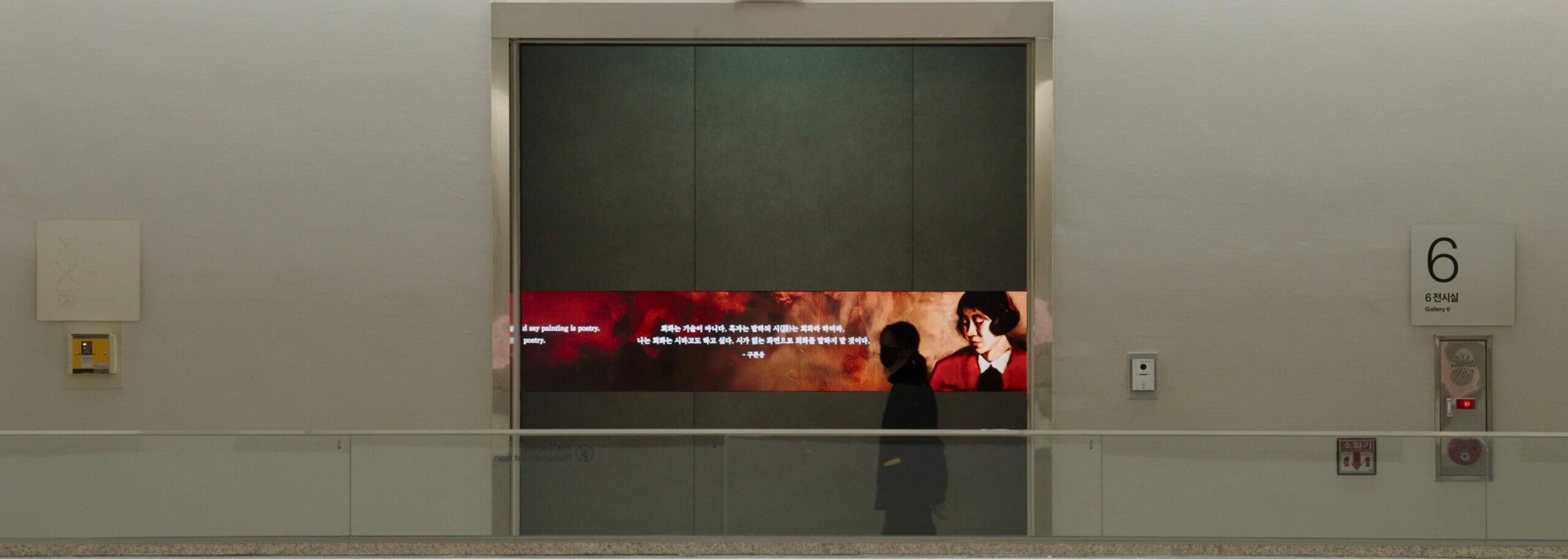

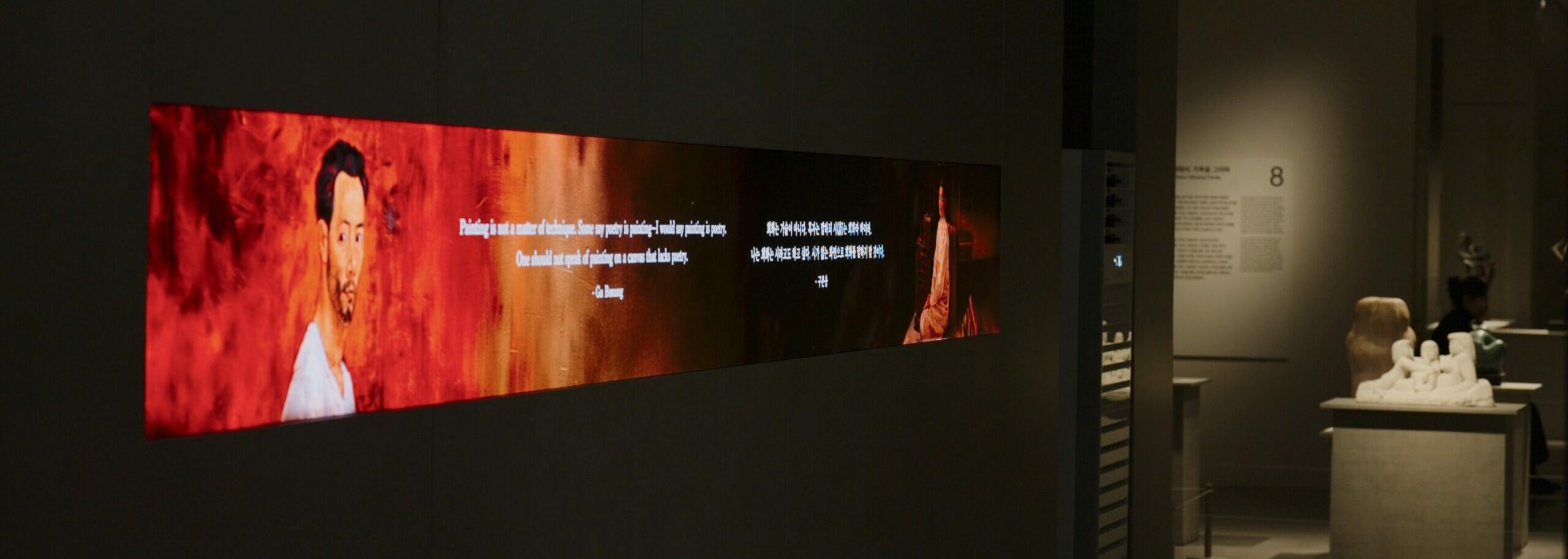

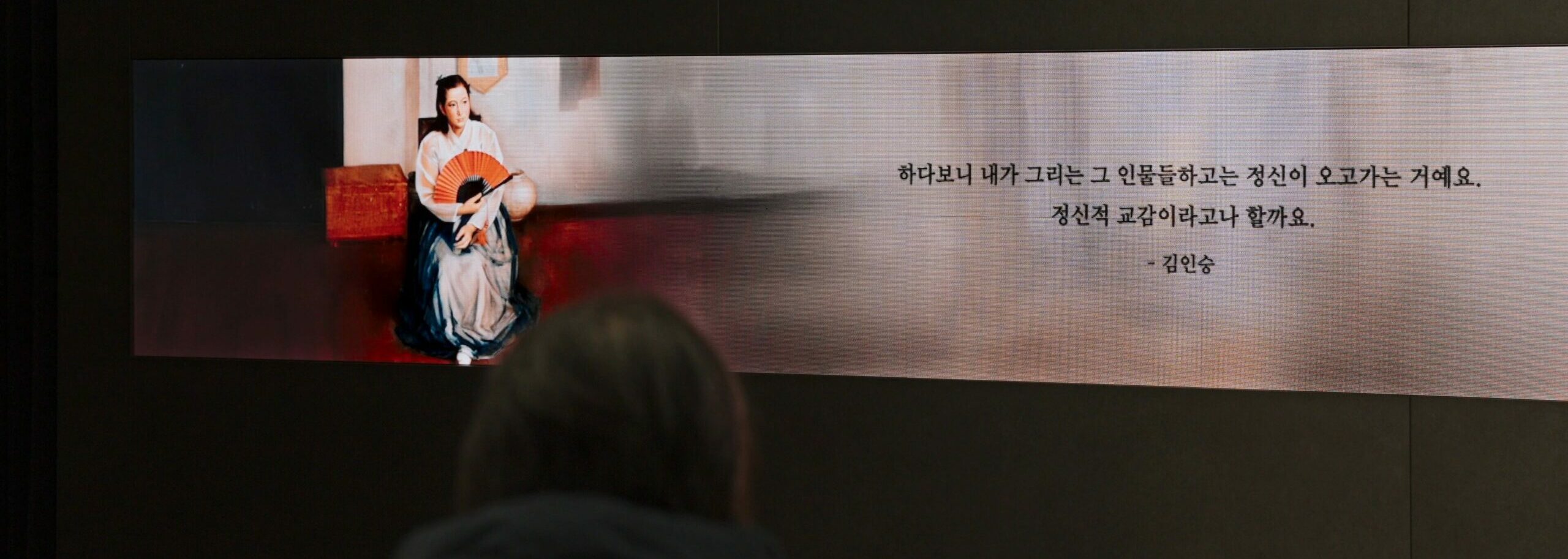

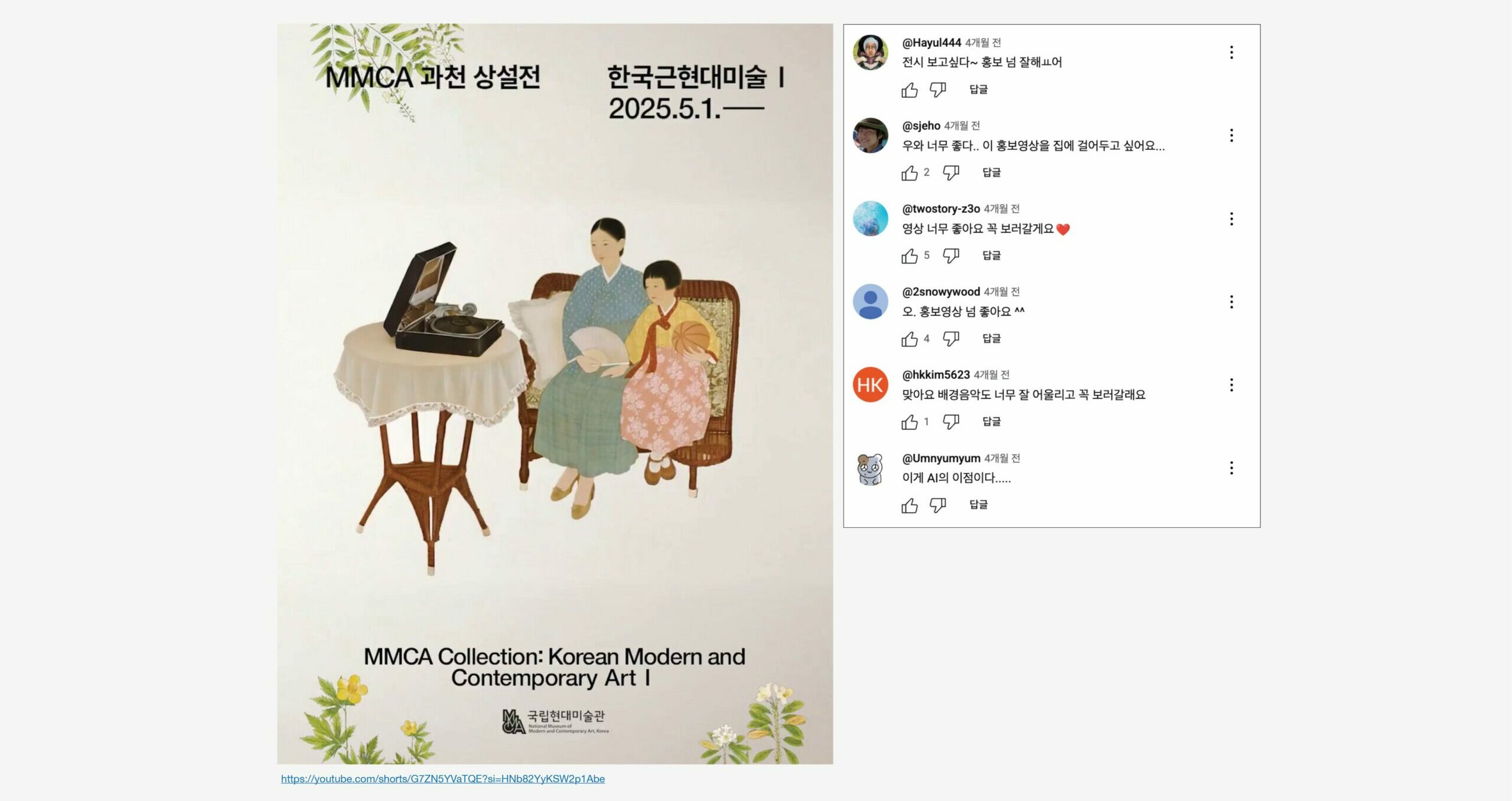

Director Lee MeeJee is the film director of 57STUDIO and the director who produced the introductory video for Korean Modern and Contemporary Art I, currently on view on the third floor. She has continued to work on archive-related projects in collaboration with major art institutions in Korea, including the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, the Seoul Museum of Art, and the Nam June Paik Art Center.

Next, I would like to introduce Professor Park Juyong. He is the author of The Future Is Not Generated and a cultural physicist. After graduating from the Department of Physics at Seoul National University and receiving his Ph.D. in statistical physics from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, he served as a researcher at Harvard Medical School and the University of Notre Dame, a visiting professor at the University of Cambridge, and the director of the Post-AI Research Institute at KAIST. He is currently researching the future of science and culture shaped by human creativity at the Graduate School of Culture Technology at KAIST.

I searched for many books related to AI at bookstores. Most of them commonly state that AI will change the world rapidly and in a frightening way, and while reading them I felt a great deal of anxiety and fear. In contrast, The Future Is Not Generated does not focus solely on AI; rather, it traverses science and art as a whole and explores the future of humanity from a humanities perspective. What are we actually expecting from AI, and what are we afraid of? And will AI truly change our world dramatically? I would like to begin with these questions.

In fact, this topic was first proposed to us by Director Lee MeeJee. She looked into various researchers and authors and specifically expressed her wish to speak with Professor Park Juyong. I also understand that she has recently attended many AI-related seminars. Is there anything in particular you reflected on while attending those seminars?

Director Lee MeeJee:

Recently, I have been attending many AI seminars because I wanted to sense the overall direction of the industry. I attended seminars in entertainment, gaming, film and video, traditional culture, and archives. What I felt was that each industry has its own perspective on AI. For example, in the entertainment industry, AI is used with an intense focus on efficiency and cost reduction. Producing effective results relative to opportunity cost seemed to be the key.

In the field of traditional culture and archives, there was significant attention on using AI for tasks that humans cannot accomplish due to physical time limitations—for example, restoration work and the classification, analysis, and statistical processing of vast amounts of archival material. In film and video, interest in AI had already existed long before we began to tangibly feel it. From the creative stage of developing scenarios to post-production and VFX, the scope of AI utilization in film and video is already very broad.

Observing these diverse perspectives, and since I work within the field of visual art, my main question became how AI should be viewed from within that field. I am particularly a practitioner who creates media content based on art archives. From a practical standpoint, AI allows me to approach specialized domains more closely and to try technologies I would not have dared to attempt before. The quality is even continuously improving.

What we learn in art school—since I come from an art school background—includes foundational areas that must be acquired through training. Even in the conceptual domain, there are stages of thinking that require training. AI, however, seems to skip stages that humans must acquire through practice. Of course, the results produced through that shortcut still need to be completed with the trained sensibility we developed in art school in order to be presentable. I personally cannot use AI outputs as they are.

Still, there are areas I would never have dared to attempt before. For example, I do not know how to work in 3D, yet now converting an image into 3D can be done with two clicks. Rendering architectural drawings was something I could not have imagined, but now it is possible. I once tried rendering an exhibition floor plan I had seen in an archive catalogue. There were no surviving photographs, but by processing the drawing through AI, I could imagine how the exhibition might have been installed at the time.

At first, these experiences were simply interesting and fascinating out of curiosity. But when I read Professor Park’s book and encountered the phrase “an elegant connection,” it resonated deeply with me. Unlike many other AI books that focus primarily on technological change, Professor Park’s book centers on the human perspective that observes those changes. For that reason, when this talk was being organized, I expressed my wish to have a conversation with him.

Curator Yi Soojung:

Then I would like to ask Professor Park. The new government speaks of becoming an AI government and staking everything on AI. Many public institutions, including our museum, feel strong pressure to engage with AI and to establish policies around it. To ask directly: will the world truly change that much?

Professor Park Juyong:

It has always been people who do the work—people generate ideas and carry out tasks. When we look at AI on the surface, it speaks like a person and produces images. It is understandable to think that a revolutionary shift is occurring.

However, we need to consider whether it truly operates in the same way as humans, beyond outward resemblance. Can it create something new in the way humans do? To address this, we must consider how AI was made.

When I ask when AI first appeared, many say it was around AlphaGo, about ten years ago. But if we look at history, references to AI-like ideas date back about three thousand years. In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, there is a description of doors that open automatically without being pushed—the first recorded automatic door. Homer initially describes such mechanisms as divine rather than human capabilities. He also describes wheeled trays that move on their own—essentially an early vision of autonomous machines. Even then, there was speculation that humans might one day achieve such technology.

That is myth. In the nineteenth century, Joseph Faber created an automaton with an artificial larynx that produced human-like speech. In 1840, people declared that human singers would become obsolete. Yet two hundred years later, that has not occurred. This reminds us to be cautious when predicting total replacement.

Modern AI emerged alongside computers. Initially, it was extremely difficult to make a computer recognize an apple or understand speech. Artificial neural networks were developed, modeled after the brain’s structure. With training on massive datasets, image recognition and speech generation became possible.

However, the path differs from human development. Humans grow through lived experience. AI is trained on enormous quantities of scraped data, repeatedly labeled until it produces correct outputs. Although the result may appear similar—identifying an apple—the path is fundamentally different.

AI performs well in domains with clear answers, such as board games where winning and losing are explicit. But in creative domains—writing, painting—there are no clear criteria of victory. It is generally recognized that AI has not yet reached the depth of lived experience necessary to produce writing that truly moves people.

When humans speak, we embed experience, intention, and judgments about truth. Large language models, by contrast, break sentences into tokens and statistically predict likely combinations. They generate text based on probability, regardless of truth or intention.

Thus, although AI increasingly replicates the outward functions of human activity, its underlying essence remains different. For that reason, we must be cautious about assuming that AI will immediately replace human life or radically transform it. Even now, we remain in a stage that requires careful consideration.