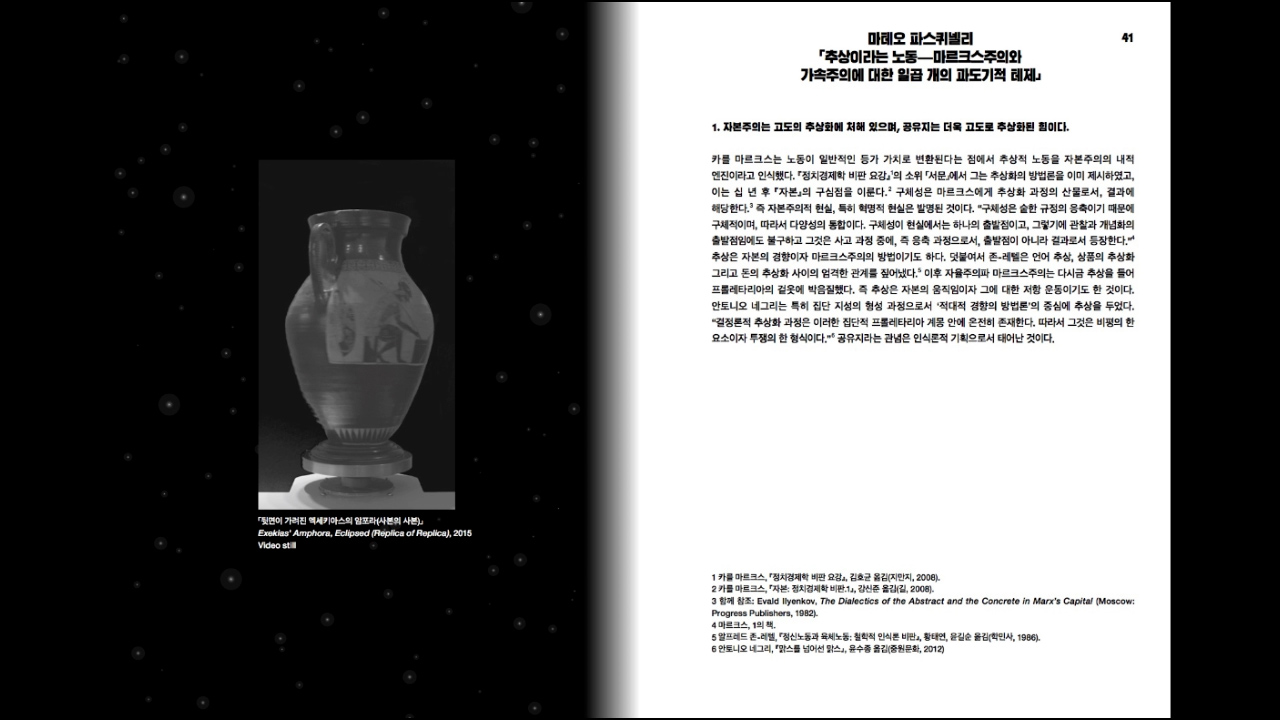

마테오 파스퀴넬리 「고향·서식지·구멍.디지털을 통한 미술의 전치」

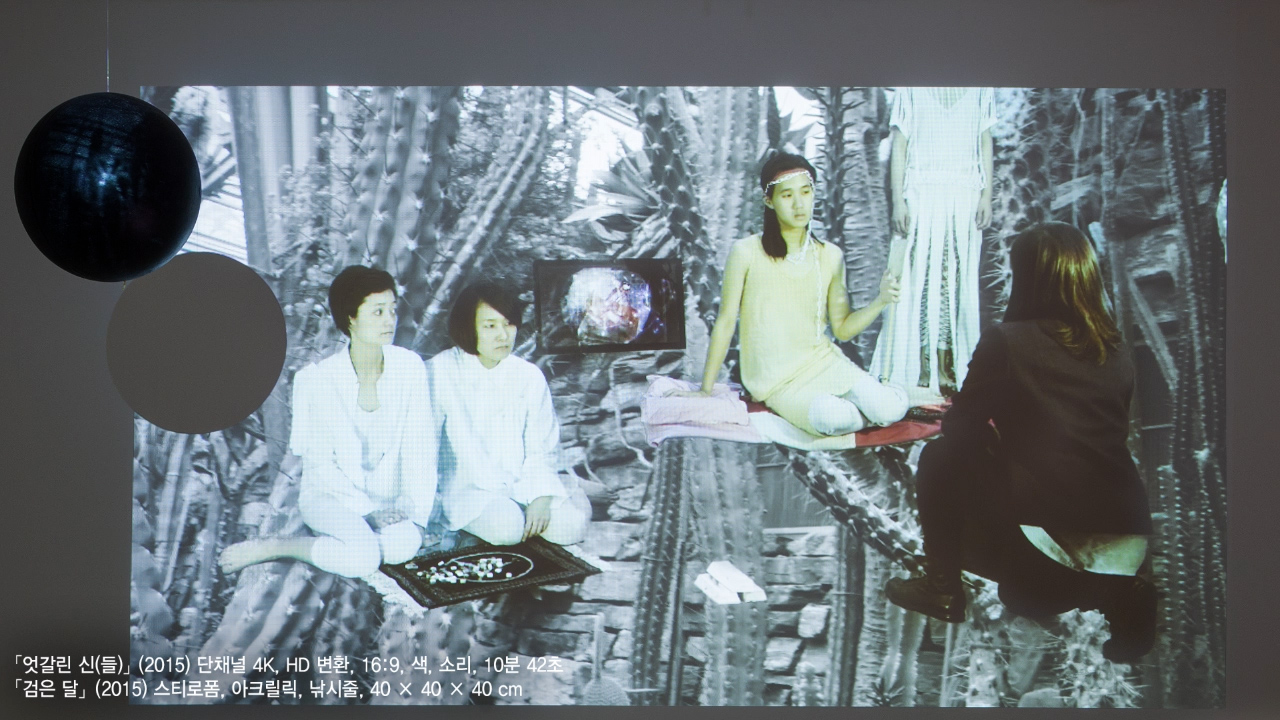

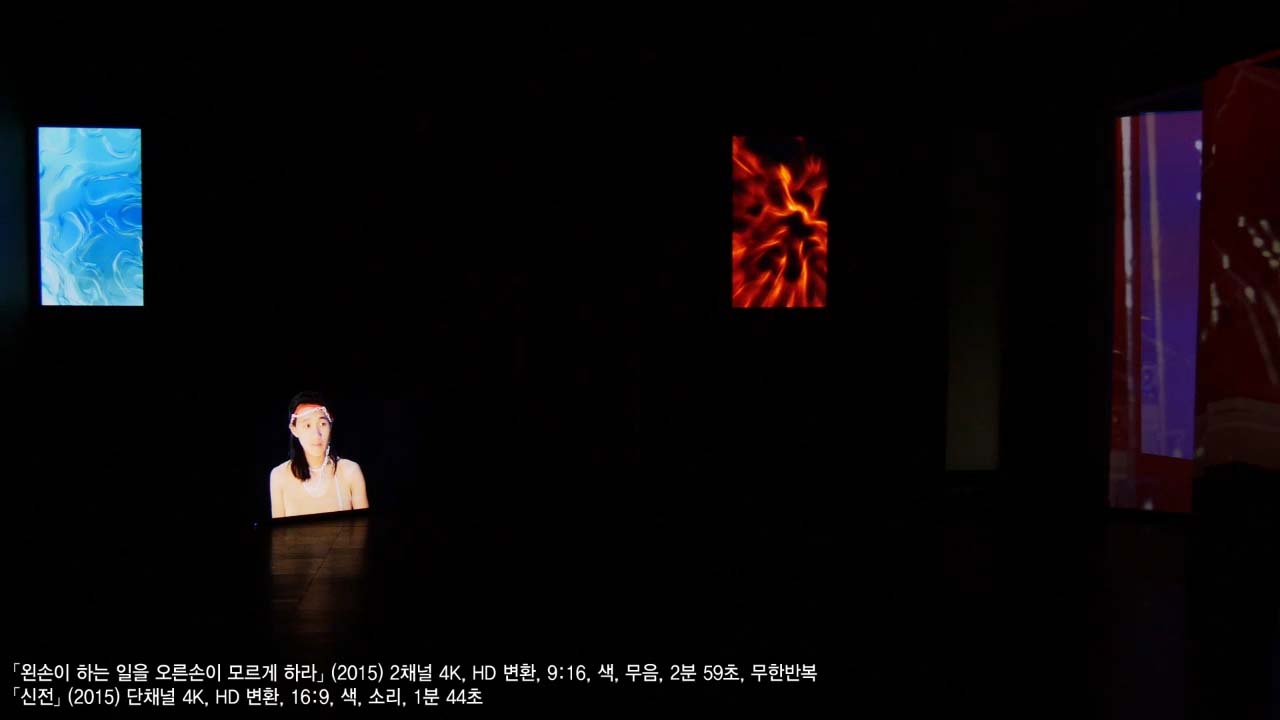

“아마도 예술은 동물이 시작한 것이다. 적어도 어떤 영토를 깎아내어 집을 짓는 동물이라면.” 언젠가 프랑스 철학자 두 사람은 이렇게 썼다.1 우리는 여기에 예술이 언제나 인간 영혼을 위한, 한시적이거나 허구적인 서식지를 투영한 것이라 덧붙일 수도 있으리라. 예술은 탐사된 적이 없는 광대한 영토와 친숙한 거처 사이의 공간을 가로질러 주거한다. 김실비는 익숙한 실존과 세계의 전망이 주는 안락한 좌표를 전치시키고자 한다. 영상 작업 「엇갈린 신(들)」의 한 대목에서 아즈텍의 젊은 마지막 왕, 몬테수마 2세는 이렇게 말한다.

어디에도 집을 갖지 못하는 사람들을 생각한다.

내가 얻은 적이 없는 집에 사는 일을 생각한다.

침략은 담을 넘으며 시작된다.

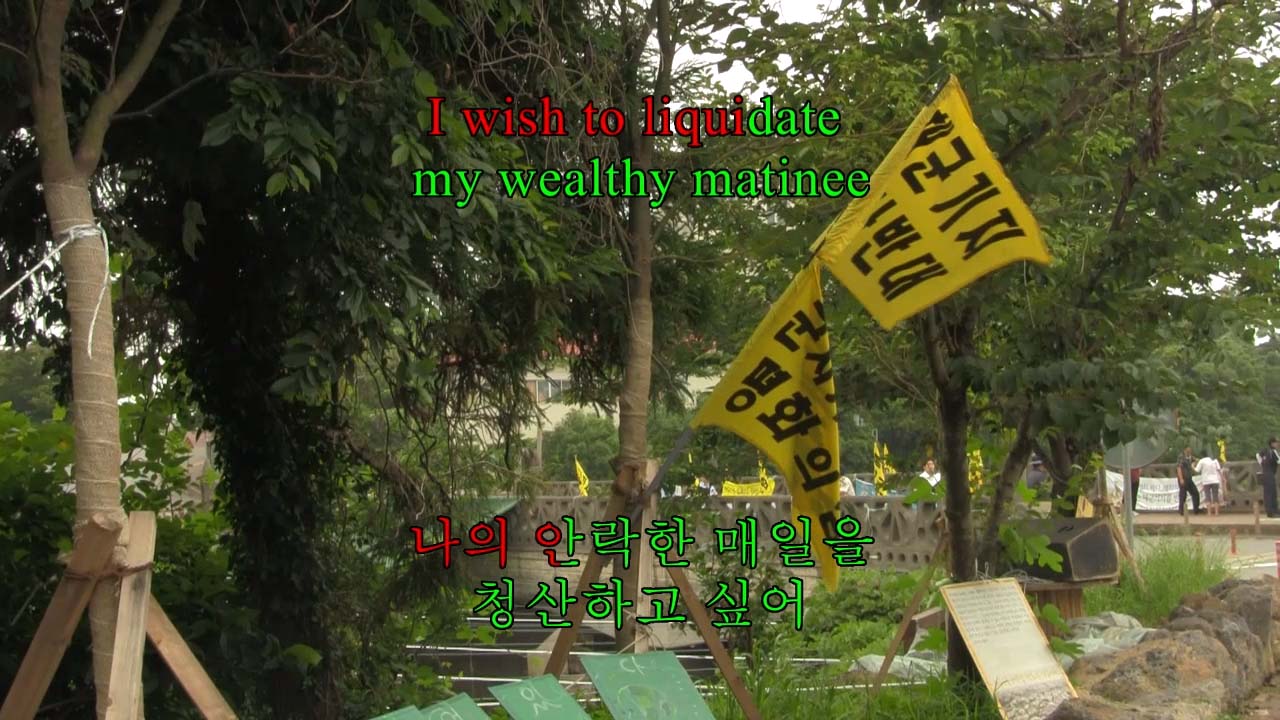

지구화 시대에 우리의 집은 어디인가. 우리의 고향Heimat은 어디에 있는가. 집이라는 감각은 늘 문제적이면서도 또 늘 필요한 것인데, 예술은 이를 어떻게 살아내고, 교란시키고, 약탈하는가. 김실비의 작업은 전지구적 디지털화가 정체성을 폭발시킨 세대의 전치감각을 흡수한 것으로 보인다. 새로운 종류의 정복자들이 당도하는 것을 숱하게 목격한 여러 도시와 서식지의 세계도 담긴다. 그리고 정복자는 점점 더 비가시적으로, 그러나 치명적으로 유입되는 자본의 꼴로 그 곳에 등장한다.

Matteo Pasquinelli “Heimat Habitat Hole: On the Digital Displacement of Art”

“Perhaps art begins with the animal, at least with the animal that carves out a territory and constructs a house,” two French philosophers once wrote.1 We may add: art is always the projection of a temporary or fictional habitat for the human soul. Art crosses and populates the space between vast unexplored territories and the familiar dwelling. Sylbee Kim displaces the reassuring coordinates of this vision of the world and of our homely existence. In her video Misread Gods, the young Moctezuma I I, the last king of the Aztecs, delivers an invocation:

Think of the people

whom no house can host.

Think of living in a house

which doesn’t belong to me.

Invasion starts

from crossing over the wall.

Where is our house in the age of globalization? Where is our homeland, our Heimat? How is art inhabiting, disrupting or looting the always-controversial and always-necessary sense of home? The work of Sylbee Kim absorbs the feeling of displacement, of a generation whose identity has been exploded by global digitization, of a world whose habitat and cities have witnessed the arrival of a new species of conquerors many times over.more and more often in the form of the invisible yet highly fatal flows of capital.