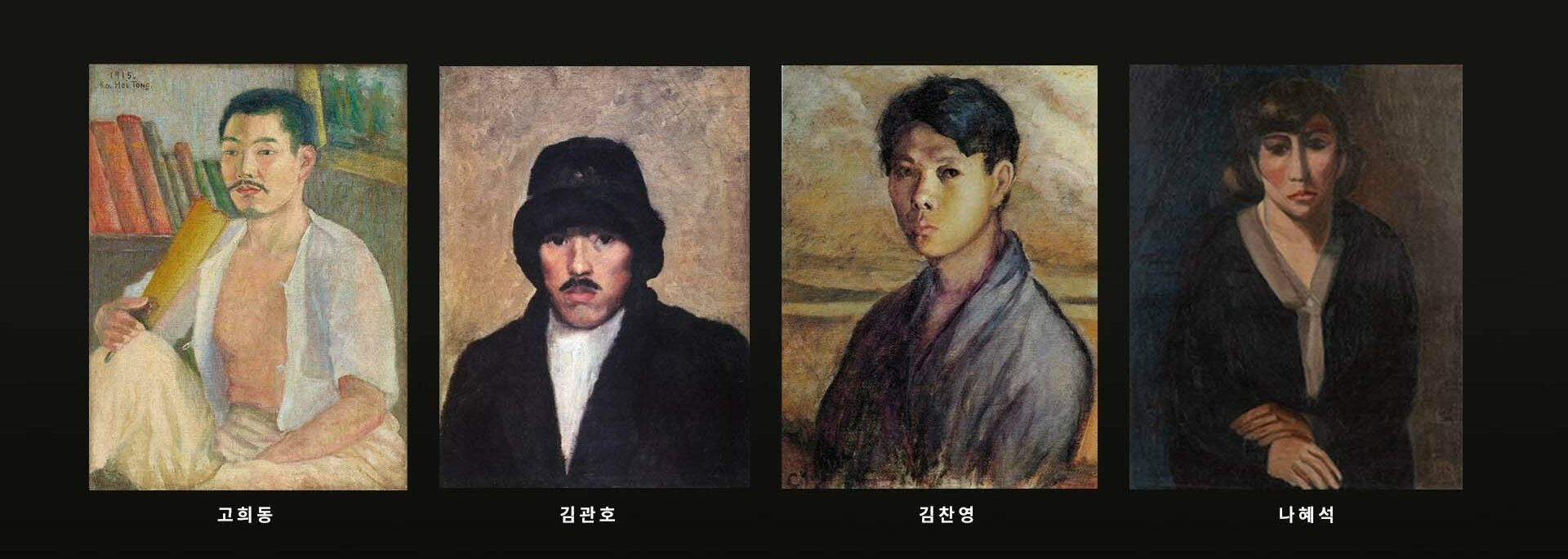

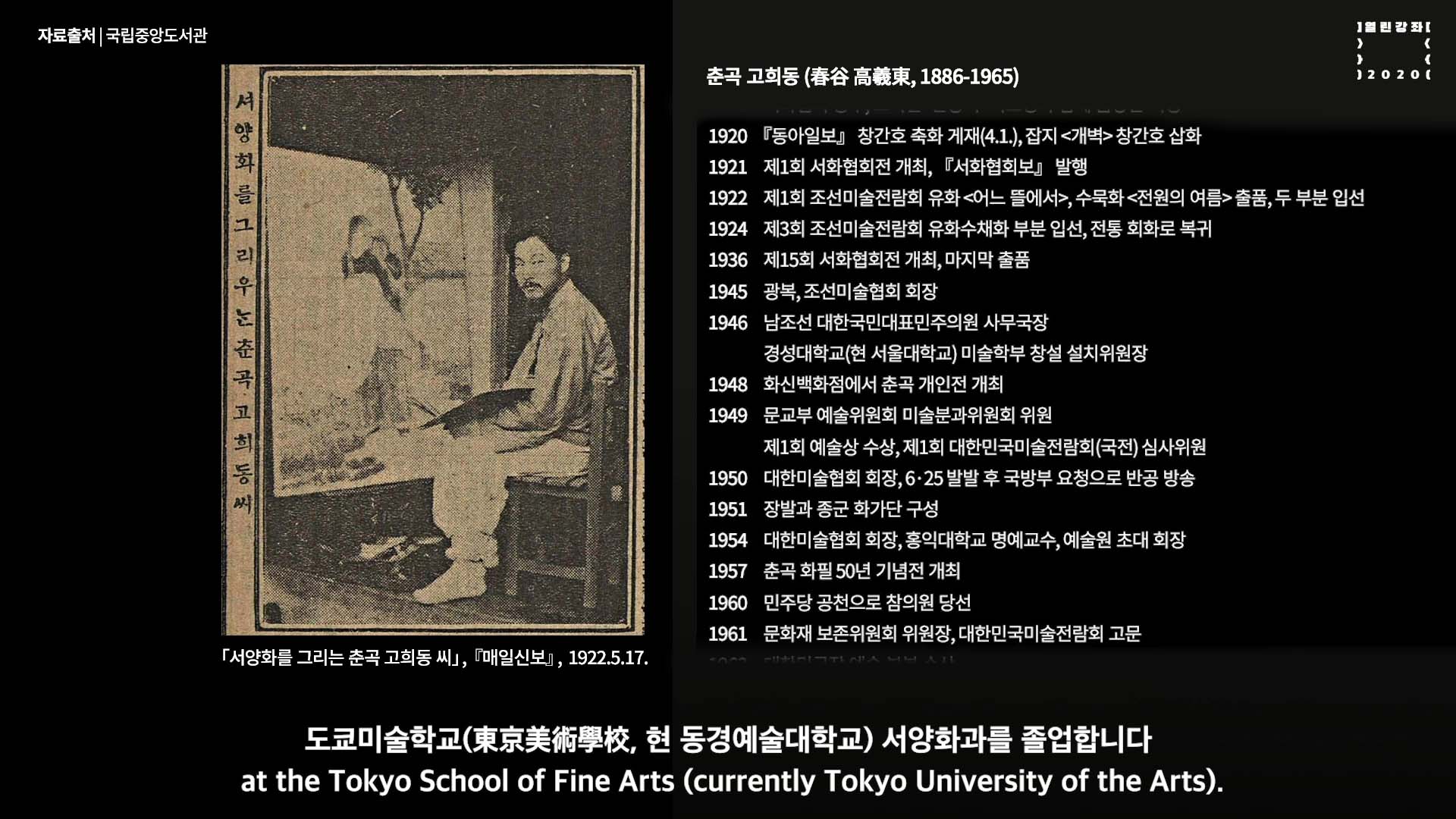

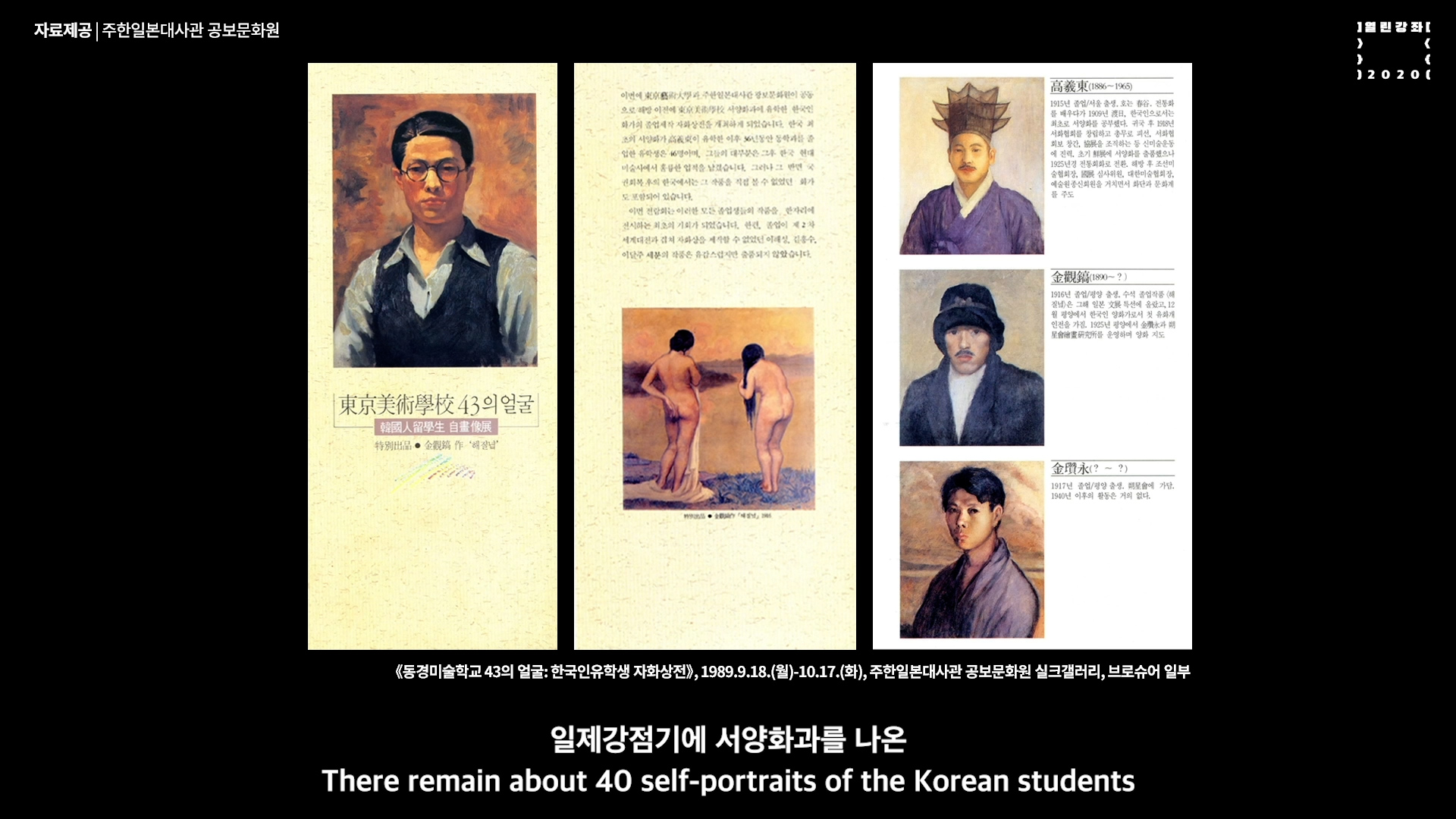

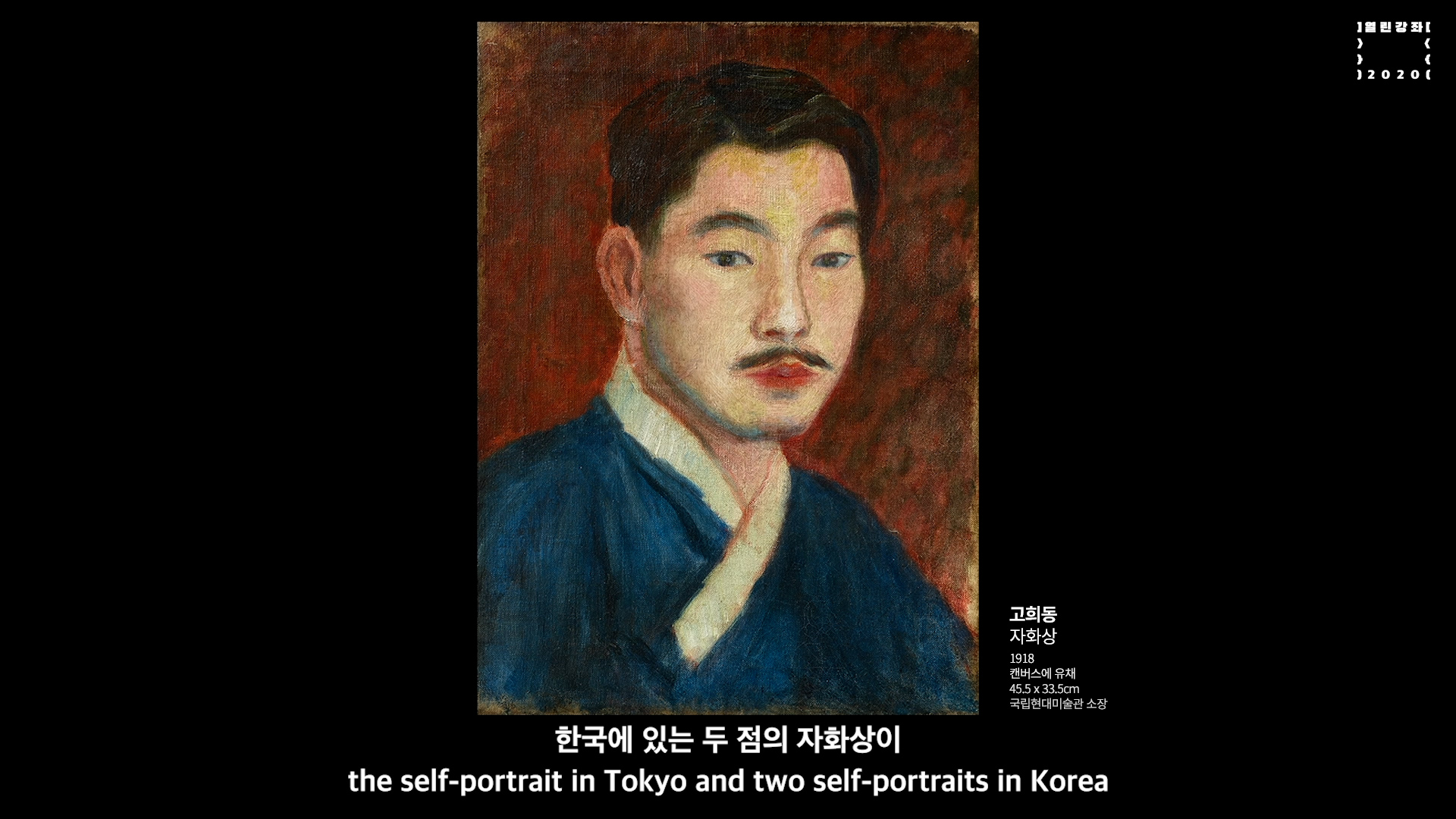

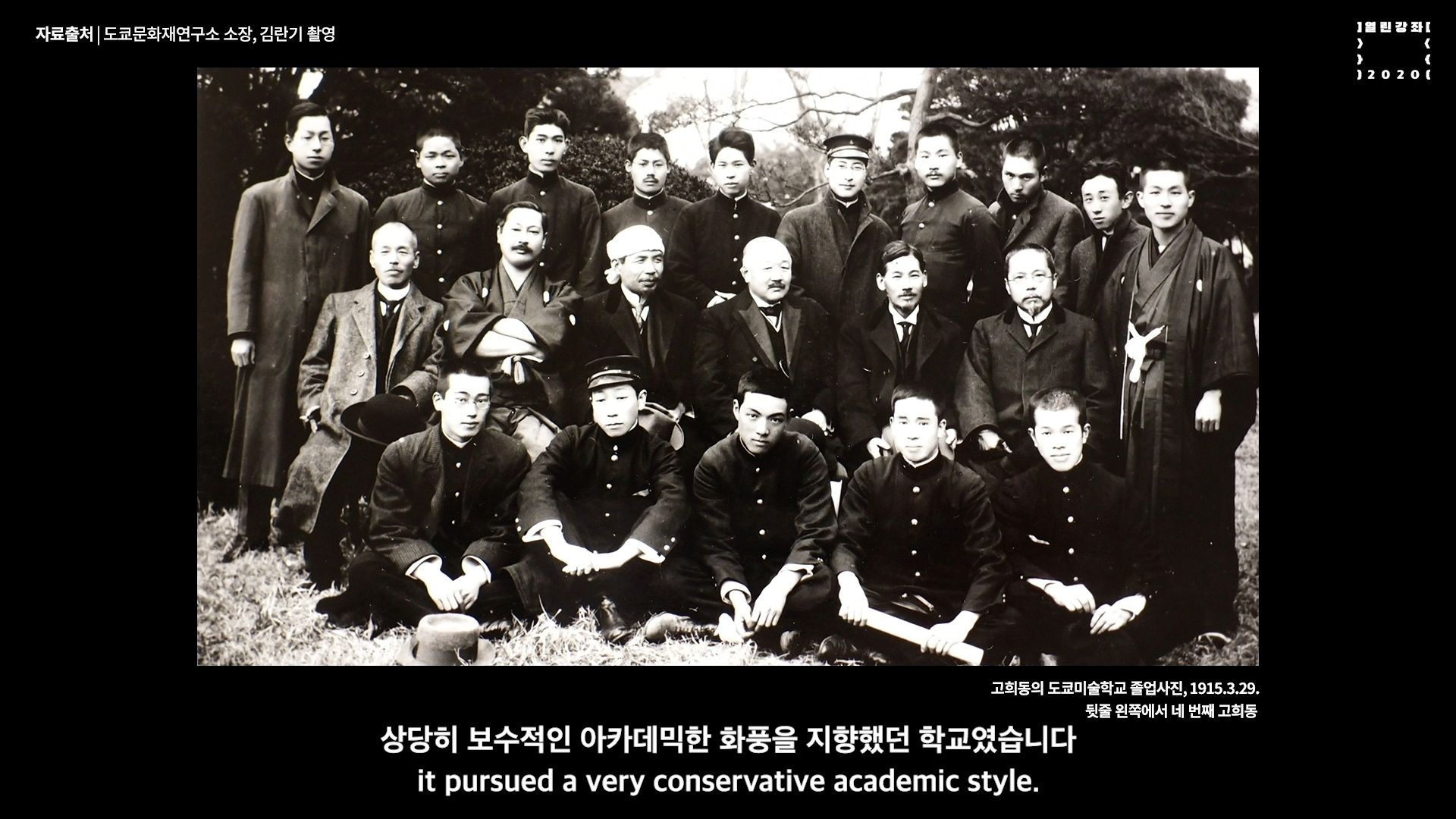

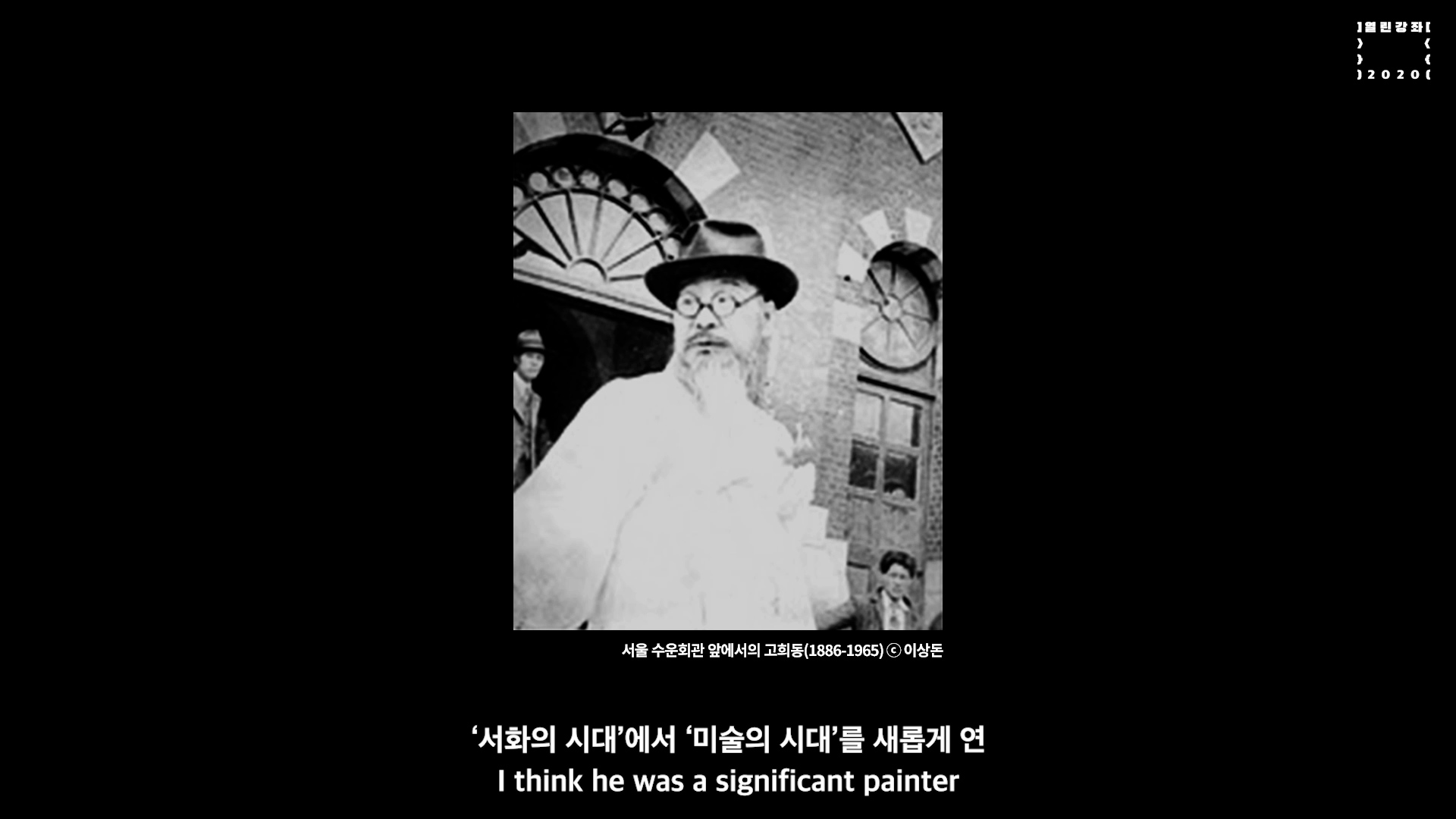

Kim Gwan-ho (1890-1959) from Pyongyang graduated from the school in 1916, and Kim Chan-young (1889-1960) who was also from Pyongyang did in 1917. All of three male artists were from wealthy families. Since the Tokyo School of Fine Arts did not accept female students, The other significant figure, Na Haesuck (1896-1948), graduated from the Tokyo Women’s School of Fine Arts instead in 1918. These four artists are pioneers of Korea who actively accepted the formal language of Western-style painting in the 1910s. Ko was from a middle class family, and he also attended ‘Hanseong French Language School.’ His family was talented in languages, and there were many official interpreters. Such a family history led Ko to learn French. Also, he grew up to be a painter, acquiring the traditional cultural practices of paper, brush, and ink under An Choongsik (1861-1919) and Cho Seokjin (1853-1920), who were the last painters of the Joseon Dynasty.

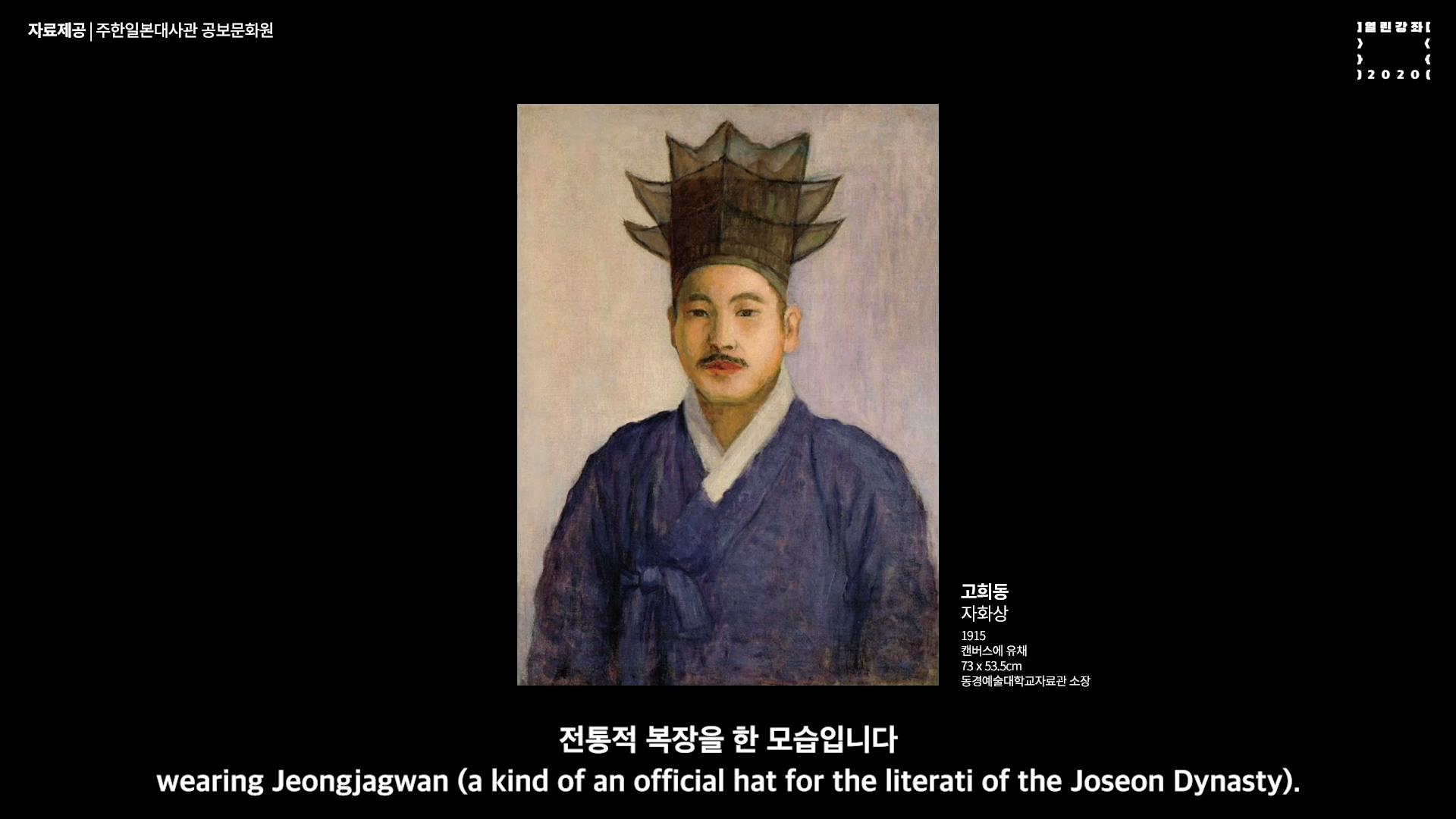

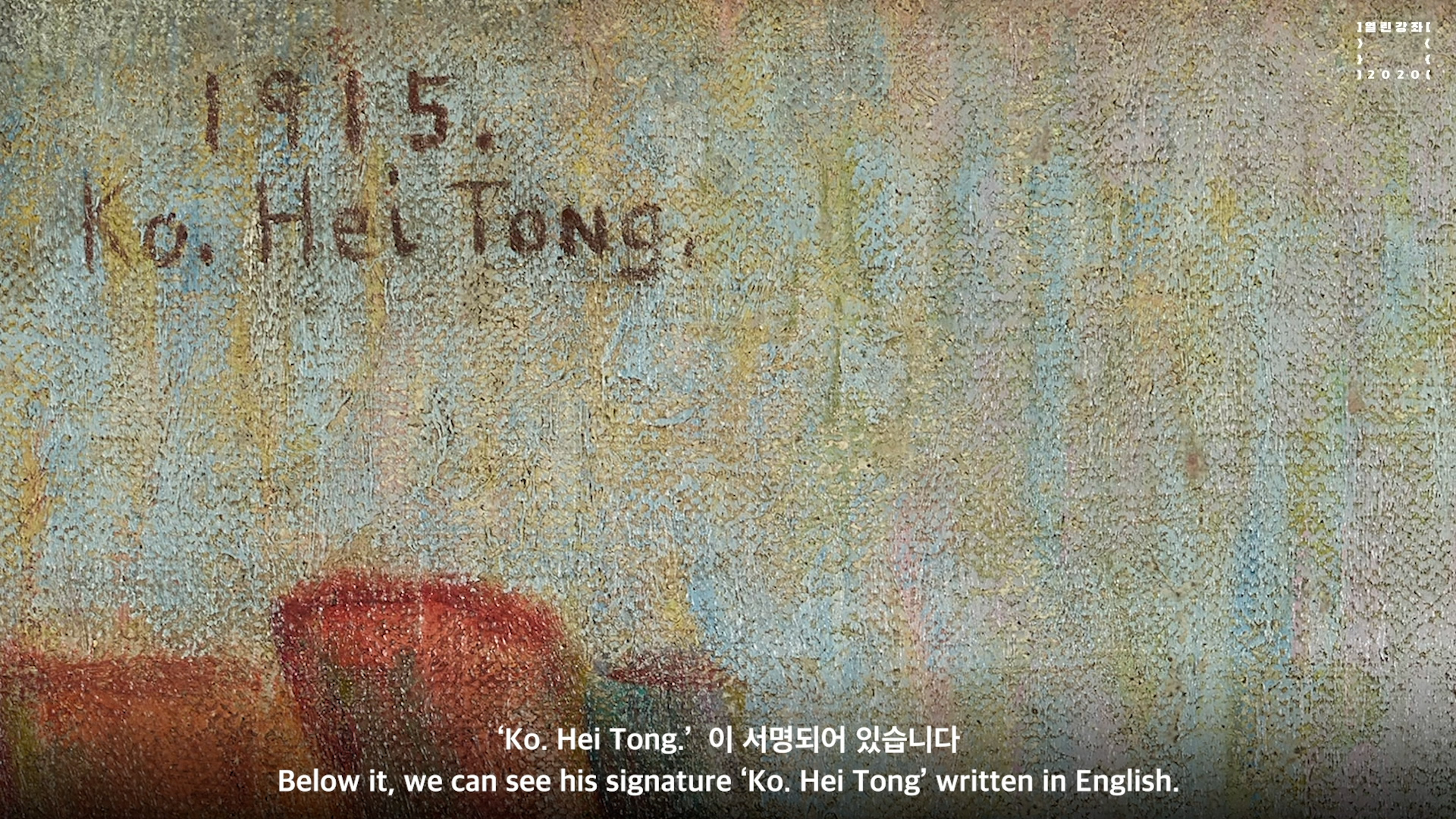

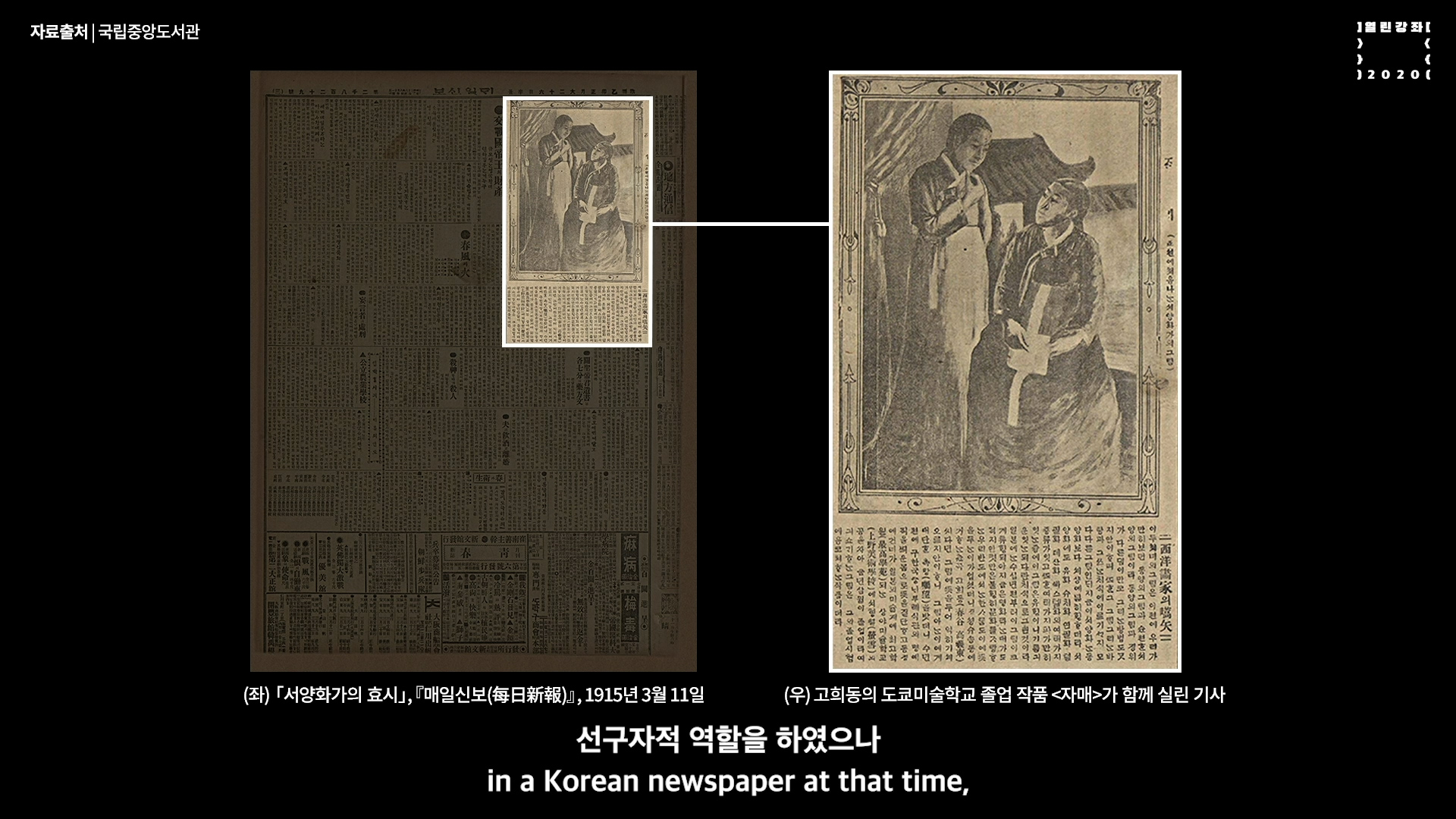

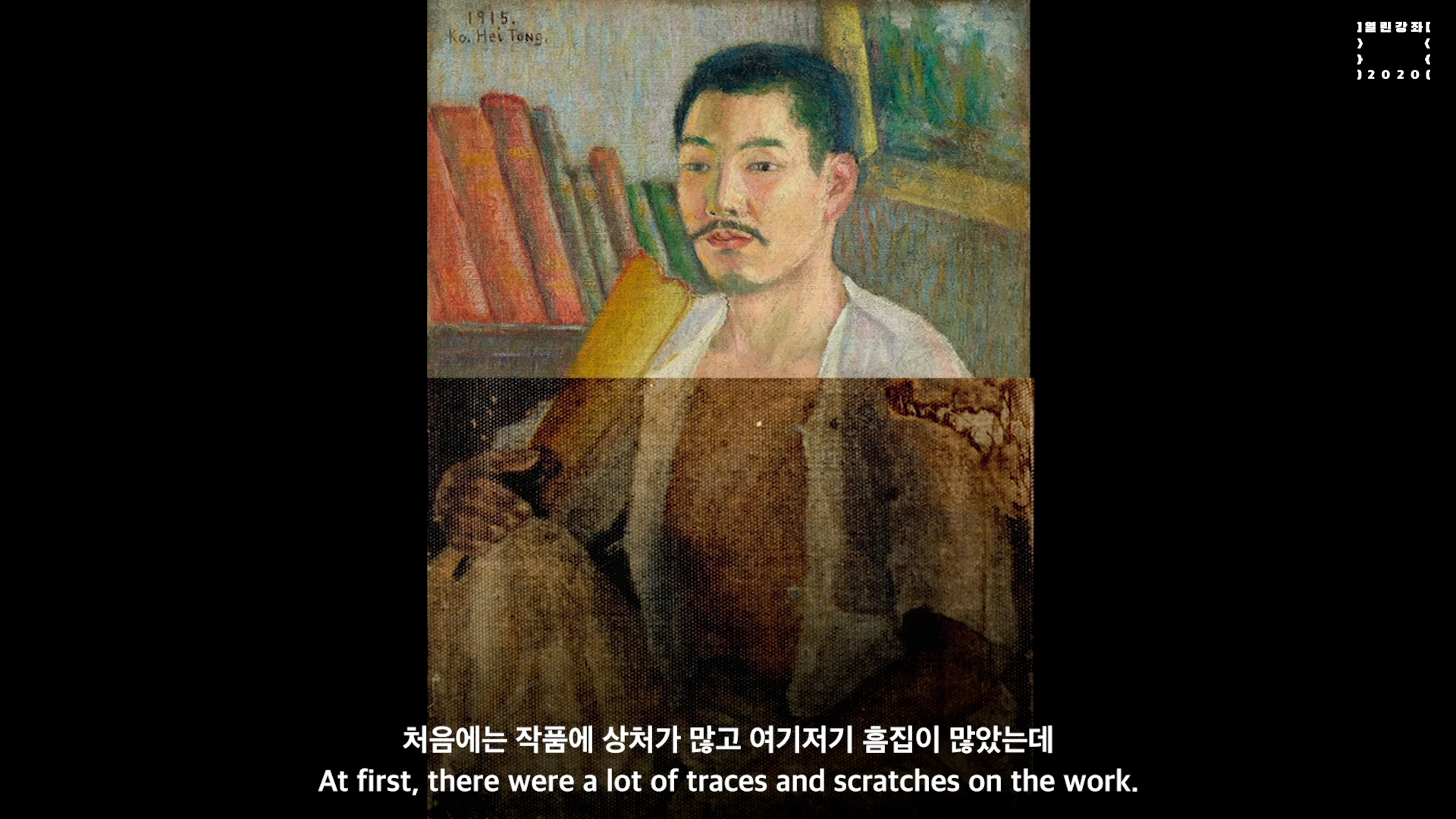

In his teens and twenties, Ko learned the unique culture of the Joseon Dynasty, that is, the idea that painting and calligraphy were inseparable. After that, he went to Tokyo and began to learn Western-style painting in earnest. At the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, all of the students submitted self-portraits in the graduation exhibition. There remain about 40 self-portraits of the Korean students who studied Western-style painting during the Japanese occupation period. The school is now called Tokyo University of the Arts.