KIM Hokyung: Hello. My name is Kim Hokyung , and I research and write about music. It’s a pleasure to meet you today.

57STUDIO: Hello. I’m from 57STUDIO, which produces archive-based video work.

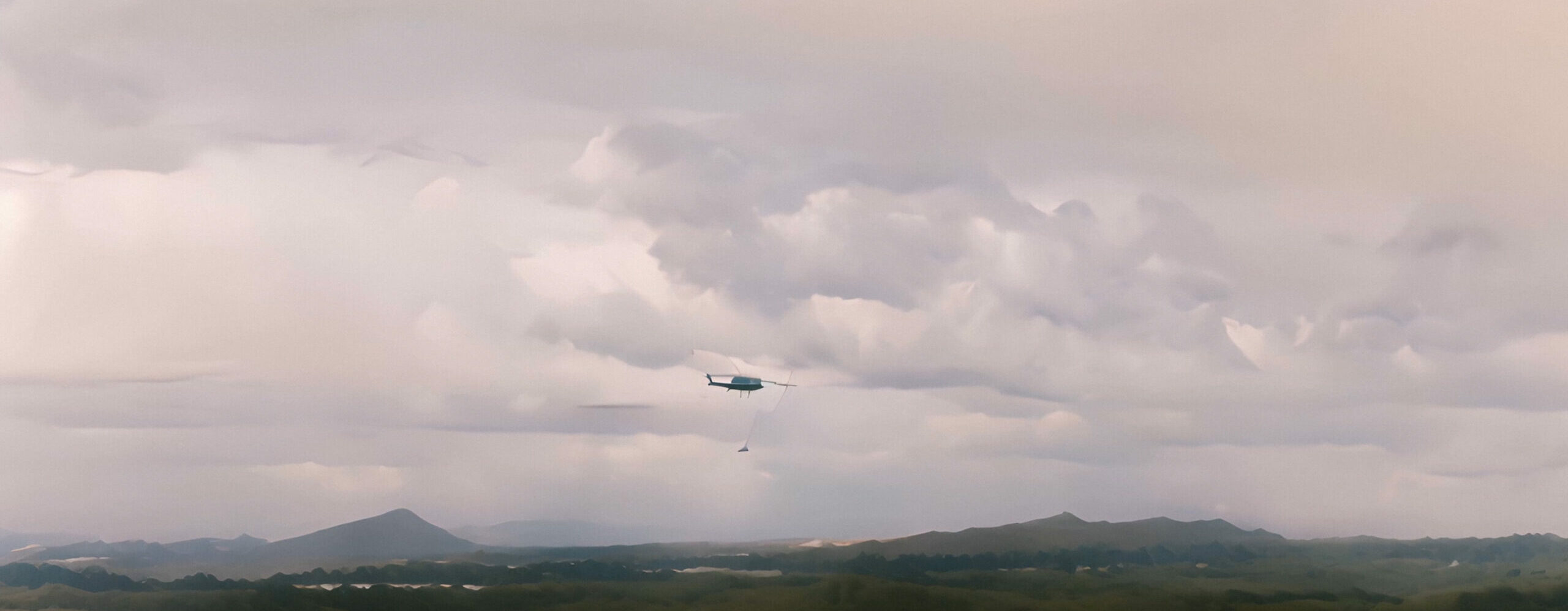

KIM Hokyung: I actually saw it before coming here, but I’d like to ask you to talk about the work Bye Bye Early Bird.

57STUDIO: We acquired images taken by photographer Lee Eunjoo depicting Nam June Paik during the last 10 years of his life, along with recordings from visits she made to his studio. Usually, when we put together a video work and receive archival materials, we try to identify with the artist and interpret the materials along those lines. Lee Eunjoo said that as she was recalling the circumstances around taking the pictures and revisiting her memories from the time, it felt like she was commemorating Nam June Paik. When I heard that and examined the materials, I found myself identifying more with Lee Eunjoo than with Paik. So when we were making this video, we thought, “Why not present it in a way that identifies with Lee Eunjoo rather than Nam June Paik?” It was shown in the last section of an archive-based exhibition, so the preceding sections had presentations with different channels showing Paik’s work in two or three channels. In the gallery. So I thought, rather than dividing [our work] into channels, we could use sound to explore the divide between the observer and the artist. When we were exhibiting the work, it was presented in a way that allowed you to view a single video two different ways, as a way of representing that divide.

KIM Hokyung: From what you describe, it sounds like there are different perspectives creating a kind of tension from the viewer’s standpoint. So how should the viewer approach the video and sounds? I found myself wondering about such points as what the right approach would be in this case. Also, you had all these different elements, But you also had the effects from the larger setting of the museum, which added a sense of pressure. So it was the kind of experience that prompted me to think about how I should be viewing it, pondering it, and gaining an understanding and sense of it. It did leave me with a lot of questions. The first has to do with what you mentioned. I wanted to ask what exactly you were anticipating with the two-channel sound approach.

57STUDIO: Nam June Paik’s videos are so outstanding. You even have The More, the Better going back online after 10 years. So the thing enabling viewers to focus on something even amid all that pressure seems to be a matter of choices. It’s similar to picking out a book at a big library and reading the introduction. Like what you said, when you leave the library, you leave with the sense of weight experienced there but also with what you read in the introduction. For me, the idea that viewers could choose which of the two sound channels to listen to was a really important aspect. When I go to a museum, I don’t study all the different works. Sometimes, there are works that I experience at a sensory level that end up making more of an impression. With Nam June Paik’s archives, there’s this enormous mixture of texts, images, and videos. Just passing through those materials, I had the sense of traveling through The More, the Better.

KIM Hokyung: So you had your mindset as the director, you had Lee Eunjoo’s perspective, and you had the artistic reinterpretation by the members of [alternative pop band] Leenalchi, who you worked with, and all of these things seemed to be layered into the context in multiple ways. I’d like to know a bit about what happened behind the scenes with the music.

57STUDIO: Getting to work with Jang Younggyu was a real honor. There’s a bit of a story there. All of us met together. We were meeting for the first time and talking about all sorts of things, then Jang asked what the work was going to be about. I had read an article where Nam June Paik said he wanted to make something with the figures of Chunhyang and Sim Cheong as protagonists. We were just kind of casually talking about that, and he seemed really drawn to that and found it fascinating. He was like, “Oh, is that so?” In the sound recordings that Lee Eunjoo made during the last 10 years of Nam June Paik’s life, you could hear what sounded like a fist banging on the keys of a piano. I shared a bit of that with [Jang], and he talked about a passage in the tale of Chunhyang where she’s imprisoned and sings as she waits for Lee Mongryong, And another in the tale of Sim Cheong where she sings before falling into the waters of Indang. He said it reminded him of that. These were different elements, but they all connected with the same feelings. As he talked about it, I just thought it was a terrific scene. So it wasn’t a case of really agonizing over the artwork. We’re musicians, so we were talking about things casually, kind of jokingly, and it ended up intertwining like braids of hair. Obviously, it’s a thrill to be able to work with such tremendous people, with people who are so talented. But being able to be there as those motifs all wove together was tremendously exciting. For me, Bye Bye Early Bird is significant as a work, but I also quite enjoyed the process.

KIM Hokyung: When you have a lot of artists working together,

in a sense, these are acts of artistic creation from different contexts, but there’s also a sense where from the present standpoint, you’re able to distinguish them as a kind of mediator. You have the figure of Nam June Paik, you have a certain artistic outcome that is already completed, and you bring those things into the present and transform them, recreating them based on your own artistic intentions and creating something in that way. I don’t know how meaningful it is to make distinctions of “artist” or “mediator,” but it did seem possible to interpret it as having created this new mediator role.

57STUDIO: As I was reading your book Playlist, one of the things I really connected with and appreciated was how you defined the role of the mediator, and in terms of what I’m doing now, I don’t know if you can call it “creation,” although I am definitely creating something in some respects, but we live in a society right now where artists are defined in terms of creation.

For someone with my role, it’s a bit uncertain what we should be defined as. So when I saw you describing that role as “mediator,” I really appreciated it. Nam June Paik talked about how if everyone had the tools to film and edit things by themselves,we would all be artists. He might have imagined at the time that we’d be carrying around these big cameras. But the fact that he mentioned it at all seemed to touch upon an innate creative urge that human beings possess.

KIM Hokyung: Now that the exhibition is finished, will the video, music, and sound elements be available for viewers to experience somewhere else?

57STUDIO: Both the sound and video end with this exhibition. As I mentioned before, the aim of the video work wasn’t exactly about communicating a specific message. After looking at Paik’s archive and Lee Eunjoo’s photographs, the final impression that we arrived at was really the main objective behind the work’s creation. So if you take it out of the museum, it loses its context. The interesting thing, though, is that you have Jang Younggyu and the other members of Leenalchi, who are performers, and they understood that this was only going to be there for that time. So once the exhibition was over, we talked ahead of time about turning the video work into a music video and presenting that. Our music videos have all been converted now using AI. You give the original image as an AI prompt, and it produces moving images that are compiled into a music video. So you can look forward to seeing the video.

KIM Hokyung: When it comes to music videos online, individual users tend to watch as they want, in situations and contexts that suit them. But it seems like there are other senses that could be expressed, too. It could also stimulate the imagination.

57STUDIO: Exactly. As you said, when the situation changes

and the context changes, even the same artwork is interpreted differently depending on when we saw it. In that sense, I seem to focus on thinking about the viewer.

KIM Hokyung: When we were talking before, one of the things you said resonated with you was when I talked about the way viewers today are understood not merely as recipients of media but as having an interactive role, playing around with art as they express their own imagination as a continuation of it. That’s one of the things I wrote, and you said that it really resonated with you.

57STUDIO: For example, the same song may sound different

based on the playlist’s title, or based on what songs you hear before and after it. There have been times when the song I wanted to hear has taken on a very different feeling. So this is really a case of the listener experiencing things through their own choices and taking on an active role. You talked about what was in the book, but there was another part I really liked. You mentioned how Annie Wong views music “not [as] a static aesthetic object but something that is always placed in a situation.” So for the music in this case, it’s currently a video, but sometimes it’s sound. That’s how I perceive it. So the question of what situation it’s placed in is not only the creator’s choice but also the choice of the experiencer. That’s the sense that I got.

KIM Hokyung: In that sense, when the new music video comes out, and moves beyond the museum’s aura into the online space, it takes on a different context, and you could view it as being a different work.

57STUDIO: Yes. That’s as far as it goes with our intentions. We obviously can’t decide what playlist it’ll be added to. Jang Younggyu and the other members of Leenalchi readily agreed to that choice, and we’re really grateful to them. I think working with them is what made this possible.